Cory Booker’s unflagging joy

The senior senator from New Jersey is one of the Democratic Party’s OGs of believing in our better angels. Where does all that optimism come from? And how can we get some?

October 30, 2024

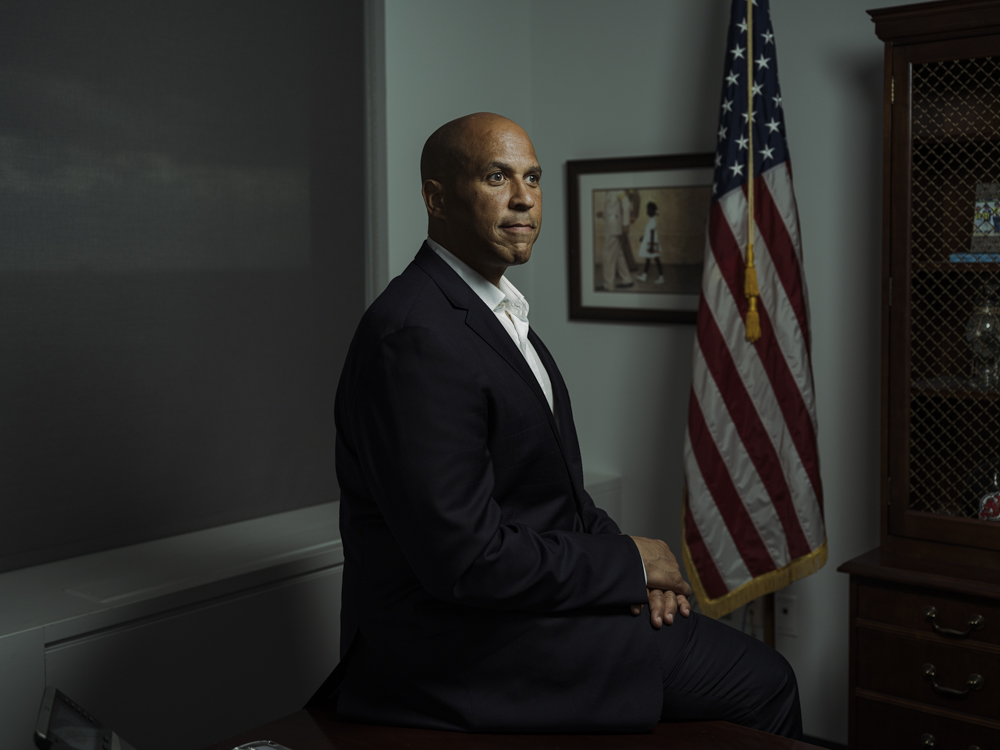

![]()

Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) at his office in downtown Newark, N.J. (Sasha Maslov for the Washington Post)

By Robin Givhan - PLAINFIELD, N.J.

On the second Sunday of August, Shiloh Baptist Church takes its morning service outside and turns West Fourth Street into the site of both a revival and a block party. The choir raises its voices; the praise dancers spin their colorful banners and congregants in rows of canvas lawn chairs and metal fellowship hall chairs listen to the Word of the Lord. For this plein-air service, choir members dress casually in tees declaring Shiloh “the place of peace” and the choir director, who has quickly sweated through his shirt, lets his powerful tenor soar skyward as he shouts: “Hallelujah!” As he does so, Sen. Cory Booker (D), the state’s once junior now senior senator, closes his eyesin the front row. The sun shines brightly on his broad shoulders and bald head, beads of perspiration erupt, and he sways to the music.

These are Booker’s constituents and he’s here to commune with them, but even if they were not, he’s in his element because this is church, and Black church in particular is about perseverance and hope. And Booker, 55, may well be the modern Senate’s most faithfully glass-half-full kind of guy. He was selling joy as a political philosophy long before the Democratic Party claimed it as their 2024 brand and essence of its White House ambitions. He’s kept his chin tilted toward the light even as former president Donald Trump shared his vision of an American “carnage” and strained our neighborly instincts.

Booker is certainly partisan, as everyone in his chamber is, but he also represents a viable model for escaping the debilitating rancor of the current moment. He does not just say he has friends on the other side of the aisle. He genuinely does.

He projects a consistent sunniness and optimism that’s hard to fake. Is he as ambitious as he ever was, even after his failed 2020 presidential bid? Yes. Is there a significant market for what he’s selling? Maybe not. He could be hopelessly naive.

Booker has been a joyful political warrior since he graduated Yale Law School in 1997. A year later, after winning a seat on Newark’s city council, Booker proceeded to sleep in a tent in the midst of a housing project strafed by violence and later in a mobile home stationed in a community struggling with crime — both acts of earnest theatricality intended to draw attention to intractable urban problems. As mayor of Newark from 2006 to 2013, his national reputation took root thanks to his prodigious use of Twitter and his extreme attentiveness to the needs of local residents. “On it!” he’d respond to concerns big and small that landed in his feed. Booker shoveled snow, helped folks get into rehab and once pulled a woman from a burning building.

![]()

While attending an outdoor church service at Shiloh Baptist Church in Plainfield, N.J., on Aug. 11, Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) stands alongside two of the young men he mentors. (Sasha Maslov for the Washington Post)

Booker stands out as the rare prominent voice on Capitol Hill who publicly, plaintively and consistently uses words like “love” as a form of political engagement. When he arrived in the Senate after winning a 2013 special election, he attended Bible study with his colleague James M. Inhofe, the late conservative Oklahoma Republican remembered as someone who characterized climate change as a hoax. Booker — a vegan — made a concerted effort to dine with Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), who considers his right to eat hamburgers practically inscribed in the Constitution. Cruz, who fellow senators seem to dislike with a rare gusto, referred to Booker as “a friend,” not just a colleague, in recent remarks on the Senate floor.

Booker calls Sen. Tim Scott, the South Carolina Republican who auditioned to be Trump’s running mate, his “brother.” Scott returned the favor: “Real friendship in DC is rare but Cory is a friend of mine! We started as the new guys in the Senate together back in 2013 and have worked on a handful of important legislation together,” he said in a statement. “We may not always agree, but we both love our country and serving the American people.”

Booker has remained undeterred in focusing on uplift rather than denigration through a pandemic, the summer of George Floyd’s murder, the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection, the painful aftermath of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, too many school shootings and a Congress that seems to be perpetually stalled on every issue that requires a moral compass and a backbone. Booker has been called a glory seeker. His critics and his chroniclers have suggested that his aggressive earnestness is little more than a performance. If so, it’s been a reality show to which he’s devoted 26 years.

So in a time of woe and uncertainty, when Trump has called America “a garbage can for the world,” we come to Booker seeking lessons of encouragement and reassurance. We come looking for the secret to his optimism. For guidance in being hopeful but also realistic.

Booker put his rejection of disillusionment on the record during Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s contentious confirmation hearing. It wasn’t the Supreme Court nominee’s Republican antagonists on the Senate Judiciary Committee who brought her to tears; it was Booker. He took 10 minutes to recognize the magnitude of her being the first Black woman nominated to the high court and to acknowledge the poise, confidence and backbone it took to navigate the highly political process.

“I’m not letting anybody in the Senate steal my joy,” Booker said with a broad smile as he bounced in his seat. “You did not get there because of some left-wing agenda. You did not get here because of some dark-money groups. You got here how every Black woman in America who has gotten anywhere has done. By being like Ginger Rogers said, ‘I did everything Fred Astaire did but backward and in heels.’”

And then Booker leaned forward and delivered a message that was both powerful and intimate. “I know what it takes for you to sit in that seat,” he said to Jackson. “You have earned this spot. You are worthy. You are a great American.”

Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson wipes away tears during remarks from Booker on the third day of her confirmation hearing. (Demetrius Freeman/The Washington Post)

The hardest thing to believe is a politician who says they just want to help — but sometimes, you want to avail yourself of Booker’s unshakable faith. On Instagram, where he has more than 1 million followers, his account overflows with videos offering up corny jokes or parables based on a serendipitous encounter on the street or train. On TikTok, where he has more than 426,000 followers, he’s an enthusiastic supporter of Vice President Kamala Harris and he has FaceTimed with donors on her behalf at a phone bank in Michigan all while solemnly reminding folks, “It’s okay not to like someone but it’s never okay to dehumanize, degrade or humiliate someone.” He’s also been campaigning — on social media and in real life — for his Senate colleague Bob Casey (D), using good-natured ribbing about sports, Wawa and pizza as Casey seeks reelection in the swing state of Pennsylvania.

In a downpour of bad news and political violence, at a time when half the country sees the other half as an existential threat to democracy, what keeps Booker from flagging? What keeps his hope vigorous from one devastating news cycle to the next? Exactly what kind of joy juice is he drinking?

First of all, Booker does not view the world through rose-colored glasses. In the aftermath of Floyd’s death, Booker recalled the lessons his elders taught him about how being a 6-foot-tall Black man should inform his interactions with police officers.

He isn’t immune to a little schadenfreude. There’s memorable video footage of Booker looking on with an expression of admiration and amusement when Harris, then a senator from California, vigorously interrogated — and flustered — William P. Barr, the former attorney general about his knowledge of and role in the Jan. 6 insurrection. And his politics can still be bruising. Just recently, Cruz accused his “friend” of engaging in junior high gamesmanship by objecting to a widely supported bipartisan bill on digital bullying and artificial intelligence that would have given Cruz a legislative win in the midst of his neck-and-neck race against Rep. Colin Allred (D-Texas), whom Booker supports.

“Absent a single substantive objection,” Cruz said, “the obvious inference is that this objection is being made because we’ve got an election in six weeks.” But sometimes, a politician has to engage in politics.

“I don’t have much patience for Pollyanna-ish, optimistic people who seem to ignore heartbreak, who seem to paint a picture that is numb and, even worse, dangerously ignorant of the suffering and struggle going on in America,” Booker said. “Hope, to me, is the active conviction that despair won’t have the last word.”

And so who is the fool? The man who argues with that? Or the people who believe it?

![]()

Booker politicking and preaching in front of the congregation at Shiloh Baptist Church during an outdoor service. (Sasha Maslov for the Washington Post)Lessons from Newark

The senator’s appearance at Shiloh Baptist Church was part of his annual summer road trip to visit each of New Jersey’s 21 counties. In the previous days, Booker had been to Cumberland County to celebrate funding for a new sewage system. He went to a fossil museum in Gloucester County and learned that one of the most significant archaeological digs in the country was a few hundred yards behind a Lowe’s. And in Atlantic County, he posed with an oversized check for $500,000 for the upkeep of Lucy the Elephant, a six-story roadside pachyderm and tourist attraction dating to 1881.

“Since I was a kid coming down to this incredible community, this elephant has stood out in my life,” said an enthusiastic Booker. “Elephants don’t forget, and neither do I. I won’t forget my childhood!”

Shiloh is in Union County. Booker lives in Newark, which is in Essex County. He’s been there for more than two decades. But he and his older brother Cary grew up about 25 miles away in the much wealthier and much Whiter town of Harrington Park. His hometown voted for George W. Bush, John McCain and Mitt Romney before finally throwing a Democrat a bone in a presidential election and supporting Hillary Clinton. Much has been written about how Booker’s parents were among the first Black employees hired by IBM, as well as among the first Black folks to buy a house in Harrington Park, which they did, in part, by sending in a White family as their surrogates.

But Booker was no stranger to Newark. He visited the city often when he was younger and talks about his political rise in Newark as his own road to Damascus — a journey of enlightenment and conversion. If there’s any singular explanation for his political philosophy, he said, it’s rooted in lessons he learned from the city, its residents and their struggles — particularly the story of Hassan Washington, a young man Booker befriended and then lost track of until Washington’s name appeared in a police report as a homicide victim.

“I could go through all these moments that Newark and my experiences there have shattered my being. And I feel shame for some of these things. I feel a lot of shame about Hassan’s death. Shahad Smith, from the same group of little boys I saw grow up, got murdered on my block while I was a senator — in 2018. Shot with an assault rifle,” Booker said. “It was like his head exploded; these bullets are not like you see in the movies. And so I carry unhealed wounds in me.”

When Booker adopted Newark as his home, the residents were predominantly Black and notably young, and the city was burdened by the same systemic ills that plagued many urban centers during the turn of the previous century, and in some cases, still do: struggling schools, violent crime, illegal drugs. Booker’s decision to move to Newark — and into an affordable housing complex named Brick Towers — was a form of radical optimism, laced with ambition and naiveté.

![]()

Booker checks his notes in the car on the way from his home in Newark to a church service at Shiloh Baptist Church. (Sasha Maslov for the Washington Post)

From his first days, through his years as mayor and even now as a U.S. senator, Newark has challenged Booker. He’s often told the story of Virginia Jones, a community activist and neighbor who became a friend, teacher and confessor. When he met Jones, she asked him to describe her neighborhood. He pointed out the crack houses, the vacant houses, the problems. She scolded him for his narrow vision, telling him that if all he could see was despair, that’s all there would ever be.

“Newark has gifted me a sense of urgency and a focus, and a deeper definition of love and forgiveness and redemption,” Booker said. “I feel like it’s afforded me, for all the mistakes I’ve made, a sense of those things. And it’s made me more forgiving of others.”

Booker no longer lives in a housing project. Brick Towers was demolished years ago. But the city gives him a regular reminder that hope grows from want rather than abundance. It grows in rocky soil. He uses stories about Newark to speak to his own fallibility, mutual forgiveness and second chances. Booker might not walk a mile every day in his constituents’ shoes, but he continues to live alongside them in a neighborhood that exists below the poverty line.

His narrow three-story flat sits shoulder to shoulder with other modest houses. His home’s only distinguishing feature is the Newark police car parked out front. It isn’t separated from the street by a moat of well-manicured grass, a circular drive or frankly, anything at all. The house is regular and unshielded from the vicissitudes of city life.

“I go home to gun violence,” Booker said. “I go home and live across the street from a drug-treatment center. I go home to realness. And people keep it real with me.”

It takes a different understanding of hope, a different magnitude of it, when you live in a community where gun violence is something you’re trying to interrupt rather than in a picket-fence idyll where you’re convinced that such terrible things could never happen. You don’t have to be particularly hopeful when the stars seem aligned in your favor. You can indulge in the petty outrages of gated communities and high-tax-bracket suburbs. Hope is what fills great chasms of need. Booker is surrounded by hopeful people. And so, he is hopeful, too.

![]()

Booker greets his mentees who surprised him at the outdoor church service at Shiloh Baptist Church. (Sasha Maslov for the Washington Post)

That’s the message Booker brought to Shiloh. After minister Danielle Brown finished her sermon, a rousing call to inclusivity and uplift that could have been a stump speech, she invited Booker to address the congregants. Dressed in a black suit and red tie, and wearing a pair of Cole Haan sneakers masquerading as wingtips, Booker moved to the lectern and without notes in hand, spoke in a raspy but booming alto.

He began with a note of praise and thanks to the minister for taking him on a spiritual journey. He emoted and enthused. He joked about his lack of children. “The Lord has not blessed me with children and I hear about it about every day from my mom, ‘When is that happening?’” He continued on to describe a phone call from the White House. “I miss Obama. And I miss her husband, too. But I really miss Obama. Michelle! Michelle! If she had married me I might be president right now.”

Then he told a story about 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, which tore through New Jersey. Booker was riding around Newark in his mobile command center; the storm was whipping the vehicle as the driver struggled to keep it on the road; and at the top of a hill littered with downed power lines, he spotted an elderly man in a yellow slicker waving a flashlight. When Booker’s car pulled up, the man explained that the scene was extremely dangerous, so he was standing on the road in the torrential weather to make sure no one was injured before emergency crews arrived.

“I had just talked to the president of the United States of America. I’d just talked to the governor of our state. I’m the mayor of the largest city. But the greatness I most saw that night,” Booker said, “was the man that was standing on that hill, holding up a light so that no one else would get hurt, risking his life.”

“No greater love has a man than this, than to give his life, than to give his life,” Booker said as his speech reached a crescendo and he moved from amateur preacher to professional politician. “We are here because of the foot soldiers for justice! Who stood on the hill! Who carried us over! Who stood in the breach! Who wept for us! Who sweat for us! Who bled for us! ”

“But now is our time. Where will we stand? Will we stand for health care? Will we stand for the right to vote? Will we stand for reproductive rights? Will we stand for public education? Will we stand with Kamala? Will we stand up and vote?

“Let us do our work,” Booker said, “because faith without work is dead.”

The minister had allotted him 10 minutes of speaking time. He came in at a respectable 11.

“There are a lot of concerns and anxieties about what we hear on television and surrounding this election,” Brown told me. “He gave people a sense of hope. A sense that we’ve made progress. And no matter what we’re seeing now, it doesn’t negate that. And if we can connect those dots, we can do even more.”

With the church service ended, the day gave way to a block party where the line to take a selfie with Booker rivaled the one for barbecue. “Look at that,” said Howard Wilson, who was taking in the scene from his lawn chair while Booker was patiently politicking in the summer heat. “He’s everything that we expected of him. Some people let politics go to their head and they forget who got them there,” said Wilson, a Shiloh member and former Newark resident. “He don’t forget. He don’t. You can talk to him.”

Don’t look to Washington

While Booker’s home in Newark is unassuming, his suite of offices on Capitol Hill is stately. The entry is marked by an exhaustive display of flags — American, New Jersey, POW, United States Senate, Intersex-Inclusive Progress Pride. Inside, the sofas are deep, the armchairs are traditional and the wood is dark. The mood is leavened with family photos, baseball caps from his and his parents’ alma maters and memorabilia celebrating Star Trek, that ultimate paean to a future filled with diversity and guided by a directive to do no harm.

On this particular day, however, his main office doors were locked. The Capitol was on high alert. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had been invited to address Congress, and the streets surrounding the Capitol were teeming with law enforcement. Just beyond the phalanx of officers, protesters were marching against the war in Gaza and America’s culpability in it.

Booker was unperturbed by the police and protesters. After all, he was in the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, when insurrectionists heave-hoed their way through locked doors, shattered windows and stalked the hallways as if they were hunting prey. If you ask Booker how he keeps his chin up in these unprecedented times — how any of us can — he will immediately challenge the premise of the question. Everything, he says, is precedented.

“Every generation has a demagogue. We just forget it. You know that the majority of Americans— I’m not talking about the number one radio show, I’m talking the majority of Americans — more than fifty percent of people went to sleep at night listening to a guy named Father Coughlin who spewed the most hateful antisemitic rhetoric,” Booker said, referring to the Catholic priest who in the 1930s voiced admiration for Hitler and Mussolini. “There were actually military leaders in the 1930s, in the midst of the Depression, when fascism was spreading in other places, U.S. military leaders were calling for a military overthrow of the country. Madison Square Garden, the Nazi Party packed it. New York! They packed it to the rafters with people chanting Nazi propaganda.”

“People talk about Brown versus the Board of Education,” the 1954 Supreme Court decision that ruled school segregation unconstitutional. “They forget that unleashed a backlash in the South that was a reign of terror,” Booker continued. “We have come through the most unimaginable possibilities. Yet every generation has had the experience my grandmother had when she was here during Obama’s inauguration.”

“She was asked by a reporter, ‘Did you ever think you would live to see a Black man about to swear [the oath of office]?’ And she said, ‘No, this is beyond my dreams.’ And would later say it was a dangerous dream to even articulate something like this. … I am so confident that when I’m 95, like my grandmother was, that we will create a reality beyond my dreams even now.”

Booker, one of four Black senators in Congress, recalled this history in his anchorman voice with soft vowels, deep inflections and a hint of gee-whiz amazement.

“I am not here because of a bunch of senators in the 1960s,” said Booker, who abruptly adopts a thick Southern drawl to impersonate South Carolina’s segregationist former senator. “You know Strom Thurmond didn’t come to the Senate floor and say, ‘I’ve seen the light. Let those Negro people have the right to vote.’”

“So when people say, ‘I’m looking to Washington for hope’ — look in the mirror for hope.”

![]()

Booker photographed at his office in downtown Newark. (Sasha Maslov for the Washington Post)

Hopeful politicking

Afew days after his New Jersey road trip, Booker was onstage at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago’s United Center rallying the crowd on behalf of his former Senate colleague. As he surveyed the audience, Booker considered the moment in the context of the country’s history.

“Look at this arena. Look around you right now,” Booker said. “We are all our ancestors’ wildest dreams.”

“There are people that doubt our collective strength. They want to tell us how bad we are. They want to say that they alone can save us,” he continued. “We know that the power of the people is greater than the people in power. And we’re not going to lose our faith.”

Booker’s insistent call for optimism echoed the sentiment of civil rights activist and former presidential candidate Jesse Jackson, now 82 and slowed by Parkinson’s, when he spoke at the 1988 Democratic convention in Atlanta and exhorted those listening to “keep hope alive.”

Booker’s disposition parallels that of former president Barack Obama, who spoke about “the audacity of hope,” during his seminal speech at the 2004 Democratic convention in Boston. He won the White House on that poetry.

Booker gavels in the program at the United Center on the third day of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. (Joe Lamberti for The Washington Post)

Booker is part of that lineage. This year, he co-sponsored a resolutionthat would, perhaps, move the country another step closer to its most dangerous dream, to an act of forgiveness and reconciliation. He called for racism to be designated a public health crisis. For Booker, the resolution isn’t a matter of blame, it’s a statement of possibility.

“It’s always come down to two teams since humanity’s beginning: The us versus them,” Booker said. The resolution aims to stop people from saying “my people, my women, my family, and have a Republican saying, ‘I’m invested in this, in solving this [maternal health] problem about why Black women are dying at higher rates. I’m invested in the problem that if a Black child and a White child have an asthma attack, the Black kid is 10 times more likely to die of the asthma attack.’”

“People don’t understand that we belong to each other,” Booker added. “We need each other.”

Booker didn’t come up as a hardscrabble activist bootstrapping it out of poverty on a wing and a prayer. He did not have an atypical, international youth with a mostly absent father. Instead, Booker embodies the traditional American ideal: a kid from a nuclear family who grew up in the suburbs.

His stubbornly fizzy style of politics feels as unlikely and implausible — and dangerous — as the very idea of America. Yet, it’s caught on again. Or at least, it hasn’t completely disappeared. That’s worth remembering. Not because the future is assured, but because it most certainly is not.

These are Booker’s constituents and he’s here to commune with them, but even if they were not, he’s in his element because this is church, and Black church in particular is about perseverance and hope. And Booker, 55, may well be the modern Senate’s most faithfully glass-half-full kind of guy. He was selling joy as a political philosophy long before the Democratic Party claimed it as their 2024 brand and essence of its White House ambitions. He’s kept his chin tilted toward the light even as former president Donald Trump shared his vision of an American “carnage” and strained our neighborly instincts.

Booker is certainly partisan, as everyone in his chamber is, but he also represents a viable model for escaping the debilitating rancor of the current moment. He does not just say he has friends on the other side of the aisle. He genuinely does.

He projects a consistent sunniness and optimism that’s hard to fake. Is he as ambitious as he ever was, even after his failed 2020 presidential bid? Yes. Is there a significant market for what he’s selling? Maybe not. He could be hopelessly naive.

Booker has been a joyful political warrior since he graduated Yale Law School in 1997. A year later, after winning a seat on Newark’s city council, Booker proceeded to sleep in a tent in the midst of a housing project strafed by violence and later in a mobile home stationed in a community struggling with crime — both acts of earnest theatricality intended to draw attention to intractable urban problems. As mayor of Newark from 2006 to 2013, his national reputation took root thanks to his prodigious use of Twitter and his extreme attentiveness to the needs of local residents. “On it!” he’d respond to concerns big and small that landed in his feed. Booker shoveled snow, helped folks get into rehab and once pulled a woman from a burning building.

While attending an outdoor church service at Shiloh Baptist Church in Plainfield, N.J., on Aug. 11, Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) stands alongside two of the young men he mentors. (Sasha Maslov for the Washington Post)

Booker stands out as the rare prominent voice on Capitol Hill who publicly, plaintively and consistently uses words like “love” as a form of political engagement. When he arrived in the Senate after winning a 2013 special election, he attended Bible study with his colleague James M. Inhofe, the late conservative Oklahoma Republican remembered as someone who characterized climate change as a hoax. Booker — a vegan — made a concerted effort to dine with Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), who considers his right to eat hamburgers practically inscribed in the Constitution. Cruz, who fellow senators seem to dislike with a rare gusto, referred to Booker as “a friend,” not just a colleague, in recent remarks on the Senate floor.

Booker calls Sen. Tim Scott, the South Carolina Republican who auditioned to be Trump’s running mate, his “brother.” Scott returned the favor: “Real friendship in DC is rare but Cory is a friend of mine! We started as the new guys in the Senate together back in 2013 and have worked on a handful of important legislation together,” he said in a statement. “We may not always agree, but we both love our country and serving the American people.”

Booker has remained undeterred in focusing on uplift rather than denigration through a pandemic, the summer of George Floyd’s murder, the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection, the painful aftermath of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, too many school shootings and a Congress that seems to be perpetually stalled on every issue that requires a moral compass and a backbone. Booker has been called a glory seeker. His critics and his chroniclers have suggested that his aggressive earnestness is little more than a performance. If so, it’s been a reality show to which he’s devoted 26 years.

So in a time of woe and uncertainty, when Trump has called America “a garbage can for the world,” we come to Booker seeking lessons of encouragement and reassurance. We come looking for the secret to his optimism. For guidance in being hopeful but also realistic.

Booker put his rejection of disillusionment on the record during Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s contentious confirmation hearing. It wasn’t the Supreme Court nominee’s Republican antagonists on the Senate Judiciary Committee who brought her to tears; it was Booker. He took 10 minutes to recognize the magnitude of her being the first Black woman nominated to the high court and to acknowledge the poise, confidence and backbone it took to navigate the highly political process.

“I’m not letting anybody in the Senate steal my joy,” Booker said with a broad smile as he bounced in his seat. “You did not get there because of some left-wing agenda. You did not get here because of some dark-money groups. You got here how every Black woman in America who has gotten anywhere has done. By being like Ginger Rogers said, ‘I did everything Fred Astaire did but backward and in heels.’”

And then Booker leaned forward and delivered a message that was both powerful and intimate. “I know what it takes for you to sit in that seat,” he said to Jackson. “You have earned this spot. You are worthy. You are a great American.”

Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson wipes away tears during remarks from Booker on the third day of her confirmation hearing. (Demetrius Freeman/The Washington Post)

The hardest thing to believe is a politician who says they just want to help — but sometimes, you want to avail yourself of Booker’s unshakable faith. On Instagram, where he has more than 1 million followers, his account overflows with videos offering up corny jokes or parables based on a serendipitous encounter on the street or train. On TikTok, where he has more than 426,000 followers, he’s an enthusiastic supporter of Vice President Kamala Harris and he has FaceTimed with donors on her behalf at a phone bank in Michigan all while solemnly reminding folks, “It’s okay not to like someone but it’s never okay to dehumanize, degrade or humiliate someone.” He’s also been campaigning — on social media and in real life — for his Senate colleague Bob Casey (D), using good-natured ribbing about sports, Wawa and pizza as Casey seeks reelection in the swing state of Pennsylvania.

In a downpour of bad news and political violence, at a time when half the country sees the other half as an existential threat to democracy, what keeps Booker from flagging? What keeps his hope vigorous from one devastating news cycle to the next? Exactly what kind of joy juice is he drinking?

First of all, Booker does not view the world through rose-colored glasses. In the aftermath of Floyd’s death, Booker recalled the lessons his elders taught him about how being a 6-foot-tall Black man should inform his interactions with police officers.

He isn’t immune to a little schadenfreude. There’s memorable video footage of Booker looking on with an expression of admiration and amusement when Harris, then a senator from California, vigorously interrogated — and flustered — William P. Barr, the former attorney general about his knowledge of and role in the Jan. 6 insurrection. And his politics can still be bruising. Just recently, Cruz accused his “friend” of engaging in junior high gamesmanship by objecting to a widely supported bipartisan bill on digital bullying and artificial intelligence that would have given Cruz a legislative win in the midst of his neck-and-neck race against Rep. Colin Allred (D-Texas), whom Booker supports.

“Absent a single substantive objection,” Cruz said, “the obvious inference is that this objection is being made because we’ve got an election in six weeks.” But sometimes, a politician has to engage in politics.

“I don’t have much patience for Pollyanna-ish, optimistic people who seem to ignore heartbreak, who seem to paint a picture that is numb and, even worse, dangerously ignorant of the suffering and struggle going on in America,” Booker said. “Hope, to me, is the active conviction that despair won’t have the last word.”

And so who is the fool? The man who argues with that? Or the people who believe it?

Booker politicking and preaching in front of the congregation at Shiloh Baptist Church during an outdoor service. (Sasha Maslov for the Washington Post)Lessons from Newark

The senator’s appearance at Shiloh Baptist Church was part of his annual summer road trip to visit each of New Jersey’s 21 counties. In the previous days, Booker had been to Cumberland County to celebrate funding for a new sewage system. He went to a fossil museum in Gloucester County and learned that one of the most significant archaeological digs in the country was a few hundred yards behind a Lowe’s. And in Atlantic County, he posed with an oversized check for $500,000 for the upkeep of Lucy the Elephant, a six-story roadside pachyderm and tourist attraction dating to 1881.

“Since I was a kid coming down to this incredible community, this elephant has stood out in my life,” said an enthusiastic Booker. “Elephants don’t forget, and neither do I. I won’t forget my childhood!”

Shiloh is in Union County. Booker lives in Newark, which is in Essex County. He’s been there for more than two decades. But he and his older brother Cary grew up about 25 miles away in the much wealthier and much Whiter town of Harrington Park. His hometown voted for George W. Bush, John McCain and Mitt Romney before finally throwing a Democrat a bone in a presidential election and supporting Hillary Clinton. Much has been written about how Booker’s parents were among the first Black employees hired by IBM, as well as among the first Black folks to buy a house in Harrington Park, which they did, in part, by sending in a White family as their surrogates.

But Booker was no stranger to Newark. He visited the city often when he was younger and talks about his political rise in Newark as his own road to Damascus — a journey of enlightenment and conversion. If there’s any singular explanation for his political philosophy, he said, it’s rooted in lessons he learned from the city, its residents and their struggles — particularly the story of Hassan Washington, a young man Booker befriended and then lost track of until Washington’s name appeared in a police report as a homicide victim.

“I could go through all these moments that Newark and my experiences there have shattered my being. And I feel shame for some of these things. I feel a lot of shame about Hassan’s death. Shahad Smith, from the same group of little boys I saw grow up, got murdered on my block while I was a senator — in 2018. Shot with an assault rifle,” Booker said. “It was like his head exploded; these bullets are not like you see in the movies. And so I carry unhealed wounds in me.”

When Booker adopted Newark as his home, the residents were predominantly Black and notably young, and the city was burdened by the same systemic ills that plagued many urban centers during the turn of the previous century, and in some cases, still do: struggling schools, violent crime, illegal drugs. Booker’s decision to move to Newark — and into an affordable housing complex named Brick Towers — was a form of radical optimism, laced with ambition and naiveté.

Booker checks his notes in the car on the way from his home in Newark to a church service at Shiloh Baptist Church. (Sasha Maslov for the Washington Post)

From his first days, through his years as mayor and even now as a U.S. senator, Newark has challenged Booker. He’s often told the story of Virginia Jones, a community activist and neighbor who became a friend, teacher and confessor. When he met Jones, she asked him to describe her neighborhood. He pointed out the crack houses, the vacant houses, the problems. She scolded him for his narrow vision, telling him that if all he could see was despair, that’s all there would ever be.

“Newark has gifted me a sense of urgency and a focus, and a deeper definition of love and forgiveness and redemption,” Booker said. “I feel like it’s afforded me, for all the mistakes I’ve made, a sense of those things. And it’s made me more forgiving of others.”

Booker no longer lives in a housing project. Brick Towers was demolished years ago. But the city gives him a regular reminder that hope grows from want rather than abundance. It grows in rocky soil. He uses stories about Newark to speak to his own fallibility, mutual forgiveness and second chances. Booker might not walk a mile every day in his constituents’ shoes, but he continues to live alongside them in a neighborhood that exists below the poverty line.

His narrow three-story flat sits shoulder to shoulder with other modest houses. His home’s only distinguishing feature is the Newark police car parked out front. It isn’t separated from the street by a moat of well-manicured grass, a circular drive or frankly, anything at all. The house is regular and unshielded from the vicissitudes of city life.

“I go home to gun violence,” Booker said. “I go home and live across the street from a drug-treatment center. I go home to realness. And people keep it real with me.”

It takes a different understanding of hope, a different magnitude of it, when you live in a community where gun violence is something you’re trying to interrupt rather than in a picket-fence idyll where you’re convinced that such terrible things could never happen. You don’t have to be particularly hopeful when the stars seem aligned in your favor. You can indulge in the petty outrages of gated communities and high-tax-bracket suburbs. Hope is what fills great chasms of need. Booker is surrounded by hopeful people. And so, he is hopeful, too.

Booker greets his mentees who surprised him at the outdoor church service at Shiloh Baptist Church. (Sasha Maslov for the Washington Post)

That’s the message Booker brought to Shiloh. After minister Danielle Brown finished her sermon, a rousing call to inclusivity and uplift that could have been a stump speech, she invited Booker to address the congregants. Dressed in a black suit and red tie, and wearing a pair of Cole Haan sneakers masquerading as wingtips, Booker moved to the lectern and without notes in hand, spoke in a raspy but booming alto.

He began with a note of praise and thanks to the minister for taking him on a spiritual journey. He emoted and enthused. He joked about his lack of children. “The Lord has not blessed me with children and I hear about it about every day from my mom, ‘When is that happening?’” He continued on to describe a phone call from the White House. “I miss Obama. And I miss her husband, too. But I really miss Obama. Michelle! Michelle! If she had married me I might be president right now.”

Then he told a story about 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, which tore through New Jersey. Booker was riding around Newark in his mobile command center; the storm was whipping the vehicle as the driver struggled to keep it on the road; and at the top of a hill littered with downed power lines, he spotted an elderly man in a yellow slicker waving a flashlight. When Booker’s car pulled up, the man explained that the scene was extremely dangerous, so he was standing on the road in the torrential weather to make sure no one was injured before emergency crews arrived.

“I had just talked to the president of the United States of America. I’d just talked to the governor of our state. I’m the mayor of the largest city. But the greatness I most saw that night,” Booker said, “was the man that was standing on that hill, holding up a light so that no one else would get hurt, risking his life.”

“No greater love has a man than this, than to give his life, than to give his life,” Booker said as his speech reached a crescendo and he moved from amateur preacher to professional politician. “We are here because of the foot soldiers for justice! Who stood on the hill! Who carried us over! Who stood in the breach! Who wept for us! Who sweat for us! Who bled for us! ”

“But now is our time. Where will we stand? Will we stand for health care? Will we stand for the right to vote? Will we stand for reproductive rights? Will we stand for public education? Will we stand with Kamala? Will we stand up and vote?

“Let us do our work,” Booker said, “because faith without work is dead.”

The minister had allotted him 10 minutes of speaking time. He came in at a respectable 11.

“There are a lot of concerns and anxieties about what we hear on television and surrounding this election,” Brown told me. “He gave people a sense of hope. A sense that we’ve made progress. And no matter what we’re seeing now, it doesn’t negate that. And if we can connect those dots, we can do even more.”

With the church service ended, the day gave way to a block party where the line to take a selfie with Booker rivaled the one for barbecue. “Look at that,” said Howard Wilson, who was taking in the scene from his lawn chair while Booker was patiently politicking in the summer heat. “He’s everything that we expected of him. Some people let politics go to their head and they forget who got them there,” said Wilson, a Shiloh member and former Newark resident. “He don’t forget. He don’t. You can talk to him.”

Don’t look to Washington

While Booker’s home in Newark is unassuming, his suite of offices on Capitol Hill is stately. The entry is marked by an exhaustive display of flags — American, New Jersey, POW, United States Senate, Intersex-Inclusive Progress Pride. Inside, the sofas are deep, the armchairs are traditional and the wood is dark. The mood is leavened with family photos, baseball caps from his and his parents’ alma maters and memorabilia celebrating Star Trek, that ultimate paean to a future filled with diversity and guided by a directive to do no harm.

On this particular day, however, his main office doors were locked. The Capitol was on high alert. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had been invited to address Congress, and the streets surrounding the Capitol were teeming with law enforcement. Just beyond the phalanx of officers, protesters were marching against the war in Gaza and America’s culpability in it.

Booker was unperturbed by the police and protesters. After all, he was in the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, when insurrectionists heave-hoed their way through locked doors, shattered windows and stalked the hallways as if they were hunting prey. If you ask Booker how he keeps his chin up in these unprecedented times — how any of us can — he will immediately challenge the premise of the question. Everything, he says, is precedented.

“Every generation has a demagogue. We just forget it. You know that the majority of Americans— I’m not talking about the number one radio show, I’m talking the majority of Americans — more than fifty percent of people went to sleep at night listening to a guy named Father Coughlin who spewed the most hateful antisemitic rhetoric,” Booker said, referring to the Catholic priest who in the 1930s voiced admiration for Hitler and Mussolini. “There were actually military leaders in the 1930s, in the midst of the Depression, when fascism was spreading in other places, U.S. military leaders were calling for a military overthrow of the country. Madison Square Garden, the Nazi Party packed it. New York! They packed it to the rafters with people chanting Nazi propaganda.”

“People talk about Brown versus the Board of Education,” the 1954 Supreme Court decision that ruled school segregation unconstitutional. “They forget that unleashed a backlash in the South that was a reign of terror,” Booker continued. “We have come through the most unimaginable possibilities. Yet every generation has had the experience my grandmother had when she was here during Obama’s inauguration.”

“She was asked by a reporter, ‘Did you ever think you would live to see a Black man about to swear [the oath of office]?’ And she said, ‘No, this is beyond my dreams.’ And would later say it was a dangerous dream to even articulate something like this. … I am so confident that when I’m 95, like my grandmother was, that we will create a reality beyond my dreams even now.”

Booker, one of four Black senators in Congress, recalled this history in his anchorman voice with soft vowels, deep inflections and a hint of gee-whiz amazement.

“I am not here because of a bunch of senators in the 1960s,” said Booker, who abruptly adopts a thick Southern drawl to impersonate South Carolina’s segregationist former senator. “You know Strom Thurmond didn’t come to the Senate floor and say, ‘I’ve seen the light. Let those Negro people have the right to vote.’”

“So when people say, ‘I’m looking to Washington for hope’ — look in the mirror for hope.”

Booker photographed at his office in downtown Newark. (Sasha Maslov for the Washington Post)

Hopeful politicking

Afew days after his New Jersey road trip, Booker was onstage at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago’s United Center rallying the crowd on behalf of his former Senate colleague. As he surveyed the audience, Booker considered the moment in the context of the country’s history.

“Look at this arena. Look around you right now,” Booker said. “We are all our ancestors’ wildest dreams.”

“There are people that doubt our collective strength. They want to tell us how bad we are. They want to say that they alone can save us,” he continued. “We know that the power of the people is greater than the people in power. And we’re not going to lose our faith.”

Booker’s insistent call for optimism echoed the sentiment of civil rights activist and former presidential candidate Jesse Jackson, now 82 and slowed by Parkinson’s, when he spoke at the 1988 Democratic convention in Atlanta and exhorted those listening to “keep hope alive.”

Booker’s disposition parallels that of former president Barack Obama, who spoke about “the audacity of hope,” during his seminal speech at the 2004 Democratic convention in Boston. He won the White House on that poetry.

Booker gavels in the program at the United Center on the third day of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. (Joe Lamberti for The Washington Post)

Booker is part of that lineage. This year, he co-sponsored a resolutionthat would, perhaps, move the country another step closer to its most dangerous dream, to an act of forgiveness and reconciliation. He called for racism to be designated a public health crisis. For Booker, the resolution isn’t a matter of blame, it’s a statement of possibility.

“It’s always come down to two teams since humanity’s beginning: The us versus them,” Booker said. The resolution aims to stop people from saying “my people, my women, my family, and have a Republican saying, ‘I’m invested in this, in solving this [maternal health] problem about why Black women are dying at higher rates. I’m invested in the problem that if a Black child and a White child have an asthma attack, the Black kid is 10 times more likely to die of the asthma attack.’”

“People don’t understand that we belong to each other,” Booker added. “We need each other.”

Booker didn’t come up as a hardscrabble activist bootstrapping it out of poverty on a wing and a prayer. He did not have an atypical, international youth with a mostly absent father. Instead, Booker embodies the traditional American ideal: a kid from a nuclear family who grew up in the suburbs.

His stubbornly fizzy style of politics feels as unlikely and implausible — and dangerous — as the very idea of America. Yet, it’s caught on again. Or at least, it hasn’t completely disappeared. That’s worth remembering. Not because the future is assured, but because it most certainly is not.