Fight Night

This Is The Story Of Jamal “Redd” Pottinger

For The Press Magazine, published on Oct 23, 2018

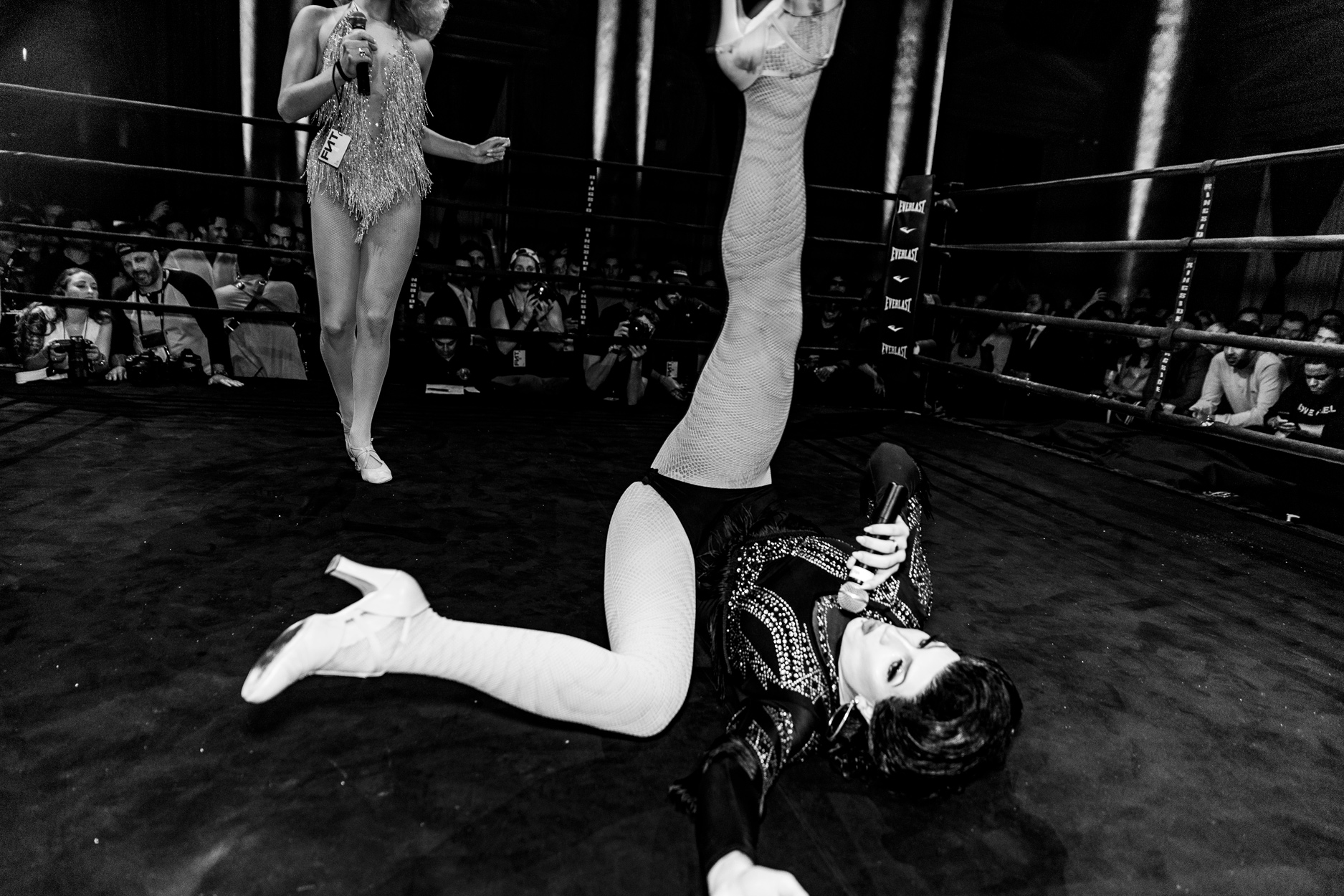

The lights are dim. The room is silent. The excitement from the crowd is palpable, but he seems to be in another place, lost in his headphones. The beat drops…ding, ding, ding…

“Before I die alone, let me have vengeance.

Before I die alone, I will have vengeance.”

Zack Hemsey’s “Vengeance” soundtrack to Denzel Washington’s Equalizer is turned up all the way on his iPhone.

He is still. His eyes are closed; adrenaline is pumping through his body. He opens his eyes but he does not look at anything specific. Instead he’s looking at his life. He’s looking at his pain. And the tears begin to fall from his eyes down to his battle scars and onto the floor beneath him. The floor that’s shaking from the raucous crowd. Hundreds of eyes are on him—eyes that see him, but have no idea what he’s capable of; eyes that don’t know who he is, that don’t know what he’s been through, that don’t care; eyes eager to see a fight.

“Nobody cares about the backdrop story. When a lion goes after a gazelle, he’s not thinking about where the gazelle came from or what happened to the gazelle. And when the gazelle is ready to defend himself, he’s not thinking if the lion is hungry or will the lion starve? Nobody cares. This is what we signed up for. We’re voluntary gladiators.”

The way Jamal tells it, it was the 1980s and he was only 3 years old when his mother began to battle crack and cocaine addiction, leaving his grandmother Barbara to be his guardian.

Despite his mother’s addiction, he claims he had a good childhood. Neither parent was in his life at the time, but he had his grandmother and his uncle Tony Morrison, who introduced him to martial arts.

“He was pretty much my father figure the whole time,” said Jamal.

While under Morrison’s wing at the Top Gun Martial Arts/The Master’s Club in Brooklyn, Jamal fought in his first karate match at age 6.

But it wasn’t the kind of fighting he wanted to do. He wanted more of the freedom of the fight, which led to conflict between him and Morrison.

“I have this rebellious spirit about me,” said Jamal, continuing, in reference to his uncle, “He’s not a bad guy at all. He’s the dude that started me off with martial arts and everything. But I don’t like following in anybody’s shadow, so I sort of went in my own route to find myself and that didn’t mesh too well with him. Everybody says me and him are pretty much the same person.”

Jamal didn’t want to be like his uncle, and his uncle didn’t want Jamal to become an MMA (mixed martial arts) fighter. Morrison wanted Jamal to follow his in path and to eventually take over one of the many karate schools he owned, ideally the Flatbush gym where Jamal grew up and still trains today.

“It wasn’t what I wanted,” said Jamal. “I always wanted to fight and to compete.”

At age 19, Jamal couldn’t make a living as a fighter; MMA wasn’t like it is now. So Jamal settled for working at a sales job, opting to do the hustle work because of the pay: $20 an hour plus commission.

But the job wasn’t for a fighter with a chip on his shoulder. Jamal said it made him literally sick staying in place. The smell of cologne and lotion that filled the office only exacerbated things for him.

So Jamal enlisted in the Marines, over the objections of many of his loved ones.

“I didn’t want to hear the bullshit,” said Jamal. “So I dealt with it on my own.”

Despite his mother’s addiction, he claims he had a good childhood. Neither parent was in his life at the time, but he had his grandmother and his uncle Tony Morrison, who introduced him to martial arts.

“He was pretty much my father figure the whole time,” said Jamal.

While under Morrison’s wing at the Top Gun Martial Arts/The Master’s Club in Brooklyn, Jamal fought in his first karate match at age 6.

But it wasn’t the kind of fighting he wanted to do. He wanted more of the freedom of the fight, which led to conflict between him and Morrison.

“I have this rebellious spirit about me,” said Jamal, continuing, in reference to his uncle, “He’s not a bad guy at all. He’s the dude that started me off with martial arts and everything. But I don’t like following in anybody’s shadow, so I sort of went in my own route to find myself and that didn’t mesh too well with him. Everybody says me and him are pretty much the same person.”

Jamal didn’t want to be like his uncle, and his uncle didn’t want Jamal to become an MMA (mixed martial arts) fighter. Morrison wanted Jamal to follow his in path and to eventually take over one of the many karate schools he owned, ideally the Flatbush gym where Jamal grew up and still trains today.

“It wasn’t what I wanted,” said Jamal. “I always wanted to fight and to compete.”

At age 19, Jamal couldn’t make a living as a fighter; MMA wasn’t like it is now. So Jamal settled for working at a sales job, opting to do the hustle work because of the pay: $20 an hour plus commission.

But the job wasn’t for a fighter with a chip on his shoulder. Jamal said it made him literally sick staying in place. The smell of cologne and lotion that filled the office only exacerbated things for him.

So Jamal enlisted in the Marines, over the objections of many of his loved ones.

“I didn’t want to hear the bullshit,” said Jamal. “So I dealt with it on my own.”

BOOM! Jamal and his unit were in battle at an undisclosed location when Jamal was injured by a mortar round, leaving him with a permanent scar on his face. The injury forced him to leave the military.

While the injury hurt, the fact that he was told to leave, after six years of serving, hurt more. Jamal torched his uniform and everything that reminded him of his time in the military. He said that leavng the Marines ignited a rage inside of him that only another form of fighting could allay.

Fight at Home

The first fight for Jamal was getting his mother sober. She was still struggling from years of drug abuse, and Jamal wasn’t going to let her die. He began training as a paramedic. Beneath his hard exterior was a pure heart determined to save the person who had brought him into the world.

After reconnecting with his mother and learning her daily routine, Jamal called on his military training to orchestrate an intervention, which played out more like a kidnapping. He gathered friends to help, picked her up off the street, and then sat her in his grandmother’s basement and forced her into a painful detox.

“It was pretty ugly,” Jamal said. “There was a lot of vomiting and shitting. She lost a lot of her body function for a while. There were so many cold sweats and screaming nights, but we got it done. She came out OK. She’s been sober since then.”

Like any fighter, after this battle was over, Jamal looked for his next fight. He passed the time by attending Long Island University, majoring in athletic training and sports science. After obtaining a master’s degree, he decided he was going to get back in the ring.

He ran into his friend Zab Judah, a former world-champion boxer. Judah put Jamal in contact with his father, Yoel Judah, who started training Jamal for his return. Soon after, Jamal bumped into an old friend, Phil Legrand, who opened the doors for him on the amateur MMA level.

Legrand asked Jamal to fight on his show “Take It to the Top,” where Jamal won the light heavyweight championship title.

While the injury hurt, the fact that he was told to leave, after six years of serving, hurt more. Jamal torched his uniform and everything that reminded him of his time in the military. He said that leavng the Marines ignited a rage inside of him that only another form of fighting could allay.

Fight at Home

The first fight for Jamal was getting his mother sober. She was still struggling from years of drug abuse, and Jamal wasn’t going to let her die. He began training as a paramedic. Beneath his hard exterior was a pure heart determined to save the person who had brought him into the world.

After reconnecting with his mother and learning her daily routine, Jamal called on his military training to orchestrate an intervention, which played out more like a kidnapping. He gathered friends to help, picked her up off the street, and then sat her in his grandmother’s basement and forced her into a painful detox.

“It was pretty ugly,” Jamal said. “There was a lot of vomiting and shitting. She lost a lot of her body function for a while. There were so many cold sweats and screaming nights, but we got it done. She came out OK. She’s been sober since then.”

Like any fighter, after this battle was over, Jamal looked for his next fight. He passed the time by attending Long Island University, majoring in athletic training and sports science. After obtaining a master’s degree, he decided he was going to get back in the ring.

He ran into his friend Zab Judah, a former world-champion boxer. Judah put Jamal in contact with his father, Yoel Judah, who started training Jamal for his return. Soon after, Jamal bumped into an old friend, Phil Legrand, who opened the doors for him on the amateur MMA level.

Legrand asked Jamal to fight on his show “Take It to the Top,” where Jamal won the light heavyweight championship title.

Fighting for Love

Shortly after, Jamal met Anastasia “Savage Beauty” Bruce at Lincoln Terrace Park in Brooklyn.

He was with his mom, showing off his fighting skills, when he saw Bruce nearby, trying to do pullups on a tree. She did two and began falling off. Jamal said she was with a “frail guy” who was trying to help her out, but he noticed they were both struggling.Jamal immediately ran over, held her up and told her to “go for it.” He wouldn’t let her stop until she reached 10 pullups.

Her endurance and perseverance prompted Jamal to ask her to join Team Redd, as he termed himself. He gave her his card, and she emailed him expressing her interest. She then became the second member of the team.

What began as a friendship quickly turned intimate. The relationship started one afternoon when Bruce paid a visit to Jamal’s gym.

“She looked phenomenal,” he said. “I couldn’t keep my eyes off of her.” The two got into a cab. Jamal’s eyes were so glued on Bruce that when it was time to pay for the ride, instead of giving the driver a $10 bill, he gave him a $50. Jamal didn’t realize his mistake until he went to give Bruce the $50 so she could go out. By then the taxi had been long gone, but the two laughed over the mishap.

“Since then we’ve been inseparable,” he said. “We were a couple for a while and then, like every good thing, we had our bad times.”

The two had a falling-out and quickly became “arch enemies.” However, Jamal said he didn’t stop training her.

“The love of martial arts and fighting is what saved our bond and relationship with each other,” he said. “To this day, we’re inseparable.”

Jamal said his appreciation for Bruce is different from his appreciation for his uncle and for Legrand.

“I have a rebellious streak against male figures,” he said. “It’s not for bad reasons. I just can’t follow someone else’s footsteps; I have to make my own path.” But Legrand saw something in Jamal that Jamal didn’t see in himself. “He didn’t have the resources to help him realize his talents,” Legrand said. Jamal’s fighting career had just begun when he ran into unexpected trouble. He was training back and forth between Brooklyn and Las Vegas when his brother, Malcolm Pottinger, got involved with people he shouldn’t have. The way Jamal tells the story, those people made up stories about his brother, saying he was running guns. They also suggested that Jamal was training people to fight for ISIS.

In Las Vegas, Jamal wasn’t doing well financially. He returned to Brooklyn and converted the garage of his grandmother’s home into a gym. Jamal began to train other fighters there as a way of making money.

FIGHT BEFORE THE FIGHIt was May 2018, just days before the Friday Night Throwdown (FNT), an organized amateur fighting circuit that started with underground boxing matches in 2008 and now features regular MMA battles around the country.

Jamal woke up abruptly. The house was shaking.The sun had barely risen when more than a dozen officers broke into his grandmother’s home using battering rams. A scared and angry Jamal ran downstairs and witnessed the officers break down the front door and hit his grandmother in the chest with the ram. He said he immediately went into defensive mode, protecting his grandmother, who suffers from heart problems. Jamal remembers fending off about five officers before he was hit in the back of the head, landed on the floor and had four AR-15s pointed at his chest.

“They destroyed the house and my gym and shattered my equipment all for nothing,” said Jamal. “My brother didn’t do anything [to warrant the police raid]. It was a lie that fucked up our whole family. Someone told a story to save their own ass.” During the bust, everyone in the house was arrested, including Jamal and his brother, grandmother, mother and mother’s boyfriend, all of whom were held at the precinct for more than 60 hours.

Once Jamal left the precinct, he went straight to the FNT. The raid and arrest had a major impact on his approach to the fight, which he would go on to regret shortly afterward.

“I used more pain and anger in that fight than anything,” said Jamal. “I felt bad because my intent was murderous. What I felt went against everything I would normally feel.” Kelvin Adams was one of Legrand’s fighters.

During that match, Jamal said he softened Adams with some light kicks and led him to believe that he was going low. When Adams dropped his hands, Jamal said he went in with a punch and Adams dropped for the first time.

“I was hoping he would stay down because I couldn’t control what was coming next,” said Jamal. “But when he got up and tried to take my head off, that, in turn, fed me more. Instead of hitting him with overhand, I hit him with an uppercut. I felt his neck snap back and I felt him go limp. I thought I killed him and I was like ‘Shit!’” Jamal said he had never fought out of a place of rage before, an extreme rage that dismayed him. Jamal said he usually fights out of a place of love.

“Everything plays an effect every time I go in the ring,” said Jamal. “I cry before every fight and it’s weird because I don’t fight out of anger; I fight out of love. I do everything out of love. It’s the main thing for me. I have a theory—the ‘love kills’ theory. When I fight, I do it for everything that I love, everything, everyone. So when I hit you with something, that’s what I’m hitting you with. Everything that’s within me, it’s everything that I’m feeling. I’m killing them with love.”

“I cry of pain, of happiness, of things that could’ve been, of what would’ve been that are not, things that shouldn’t be but are,” he said.

FIGHTING FOR GLORY

While professional fighters like Floyd Mayweather strive for fame and money, Jamal said all he wants is the glory. “I wish I was as hungry for money as everyone else,” said Jamal. “I think I’d be extremely rich right now if I was. But I look more for the glory. I love this shit. This is what I do. I know the world is going to know my name.”

On October 13, Jamal went pro at Bellator MMA, an American mixed martial arts promotion based in Santa Monica, California. “I'm stoked but petrified at the same time,” Jamal told us before the fight. “The uncertainty and the thrill of it blends with a mix of sorrow. I’ve waited all of my life for this moment and now that it's here, I'm sort of wondering if I'm really ready for it.”

Jamal said that no matter what, he’s not going to give up. “I'm gripping it, biting down and getting ready to run the gauntlet,” he said. “It’s time to let the world know that I'm here now and things are about to change. The wolf is at the gates and he won’t leave.”

Jamal said his past is what fuels him, but his future is what keeps the fight in him alive. The 33-year-old added that his age is irrelevant. “Age is a number,” he said. “As you get older, you get stronger, wiser and smarter.”

He used Bernard Hopkins as an example, saying the famous boxer, who is now 53 years old, is still “putting people out.” Jamal said he plans to fight until he can’t any longer, whether it be a physical fight or one in another field such as law enforcement, which is a dream of his.In November 2017, Jamal submitted his application to the Las Vegas Police Department, but was denied because of alleged nonpayment of his student loans. He was instructed to try again in 2020.

“The best thing about being denied is that it might’ve saved me from something that wasn’t meant to be,” said Jamal. Jamal said he still harbors some hostility towards law enforcement since the police raid of his grandmother’s home, but that he’s working on it. “I have to realize that it was just that batch; it wasn’t every officer,” he said.

But until he decides to join another fight, he will continue to strive for success in the professional MMA industry.

“Nobody is going to help me right now,” Jamal concluded. “Nobody is going to be my hero. I have to save myself.”

While professional fighters like Floyd Mayweather strive for fame and money, Jamal said all he wants is the glory. “I wish I was as hungry for money as everyone else,” said Jamal. “I think I’d be extremely rich right now if I was. But I look more for the glory. I love this shit. This is what I do. I know the world is going to know my name.”

On October 13, Jamal went pro at Bellator MMA, an American mixed martial arts promotion based in Santa Monica, California. “I'm stoked but petrified at the same time,” Jamal told us before the fight. “The uncertainty and the thrill of it blends with a mix of sorrow. I’ve waited all of my life for this moment and now that it's here, I'm sort of wondering if I'm really ready for it.”

Jamal said that no matter what, he’s not going to give up. “I'm gripping it, biting down and getting ready to run the gauntlet,” he said. “It’s time to let the world know that I'm here now and things are about to change. The wolf is at the gates and he won’t leave.”

Jamal said his past is what fuels him, but his future is what keeps the fight in him alive. The 33-year-old added that his age is irrelevant. “Age is a number,” he said. “As you get older, you get stronger, wiser and smarter.”

He used Bernard Hopkins as an example, saying the famous boxer, who is now 53 years old, is still “putting people out.” Jamal said he plans to fight until he can’t any longer, whether it be a physical fight or one in another field such as law enforcement, which is a dream of his.In November 2017, Jamal submitted his application to the Las Vegas Police Department, but was denied because of alleged nonpayment of his student loans. He was instructed to try again in 2020.

“The best thing about being denied is that it might’ve saved me from something that wasn’t meant to be,” said Jamal. Jamal said he still harbors some hostility towards law enforcement since the police raid of his grandmother’s home, but that he’s working on it. “I have to realize that it was just that batch; it wasn’t every officer,” he said.

But until he decides to join another fight, he will continue to strive for success in the professional MMA industry.

“Nobody is going to help me right now,” Jamal concluded. “Nobody is going to be my hero. I have to save myself.”

Text by Ariel Hernandez