Meet Lu Jun, One of China’s Most Wanted Social Activists

Leader of influential Chinese nonprofit is target of Beijing campaign against Western values

for the Wall Street Journal, published on Sept 6, 2015

BEIJING—During the nearly 50 interrogation sessions Chinese women’s rights activist Li Tingting says she endured during the month-plus she spent in a Beijing detention center, security agents raised one name more than any other.

“Lu Jun. They said Lu Jun was using me,” says Ms. Li, one of five young female activists who were criminally detained this spring while planning anti-sexual harassment protests ahead of International Women’s Day. “They talked about him endlessly.”

Mr. Lu, one of China’s most effective social campaigners of the past decade, is a primary target in a sweeping civil society crackdown that appears to have dramatically narrowed the space for even moderate dissent in the country.

It comes as the driving force behind the Communist Party’s legitimacy in recent decades—economic growth—has begun to flag. Ballooning debt, a plunging stock market and capital flight have raised questions about Beijing’s ability to shore up growth, increasing the chances of social discord and making Chinese President Xi Jinping more eager to clamp down on critics.

While government suppression of activism isn’t new in China, the current campaign has expanded beyond overt critics of the state to target those, like Mr. Lu and his organization Yirenping, who have succeeded by working within the rules set by authorities.

“It’s a realignment of society. They want all of these social interactions to be filtered through the party,” said the Beijing-based director of a foreign nonprofit that has worked with Yirenping, who didn’t want to be identified because of the political danger of speaking out.

The crackdown is heightening U.S. concerns over China’s human rights conditions, about which U.S. officials say President Barack Obama is likely to confront Mr. Xi during a Washington summit this month. The State Department is also considering whether to boycott a United Nations meeting on women’s rights later in the month that China is co-hosting and where Mr. Xi is expected to speak, say the officials.

Since May last year, as many as a dozen of Mr. Lu’s close associates and former staff have been detained, interrogated or expelled from the country. Police have raided his office in Beijing and that of a sister organization in another city, Mr. Lu says. Of the five female activists detained in March, three were current or former employees of Mr. Lu.

Mr. Lu, one of China’s most effective social campaigners of the past decade, is a primary target in a sweeping civil society crackdown that appears to have dramatically narrowed the space for even moderate dissent in the country.

It comes as the driving force behind the Communist Party’s legitimacy in recent decades—economic growth—has begun to flag. Ballooning debt, a plunging stock market and capital flight have raised questions about Beijing’s ability to shore up growth, increasing the chances of social discord and making Chinese President Xi Jinping more eager to clamp down on critics.

While government suppression of activism isn’t new in China, the current campaign has expanded beyond overt critics of the state to target those, like Mr. Lu and his organization Yirenping, who have succeeded by working within the rules set by authorities.

“It’s a realignment of society. They want all of these social interactions to be filtered through the party,” said the Beijing-based director of a foreign nonprofit that has worked with Yirenping, who didn’t want to be identified because of the political danger of speaking out.

The crackdown is heightening U.S. concerns over China’s human rights conditions, about which U.S. officials say President Barack Obama is likely to confront Mr. Xi during a Washington summit this month. The State Department is also considering whether to boycott a United Nations meeting on women’s rights later in the month that China is co-hosting and where Mr. Xi is expected to speak, say the officials.

Since May last year, as many as a dozen of Mr. Lu’s close associates and former staff have been detained, interrogated or expelled from the country. Police have raided his office in Beijing and that of a sister organization in another city, Mr. Lu says. Of the five female activists detained in March, three were current or former employees of Mr. Lu.

Leading from afar

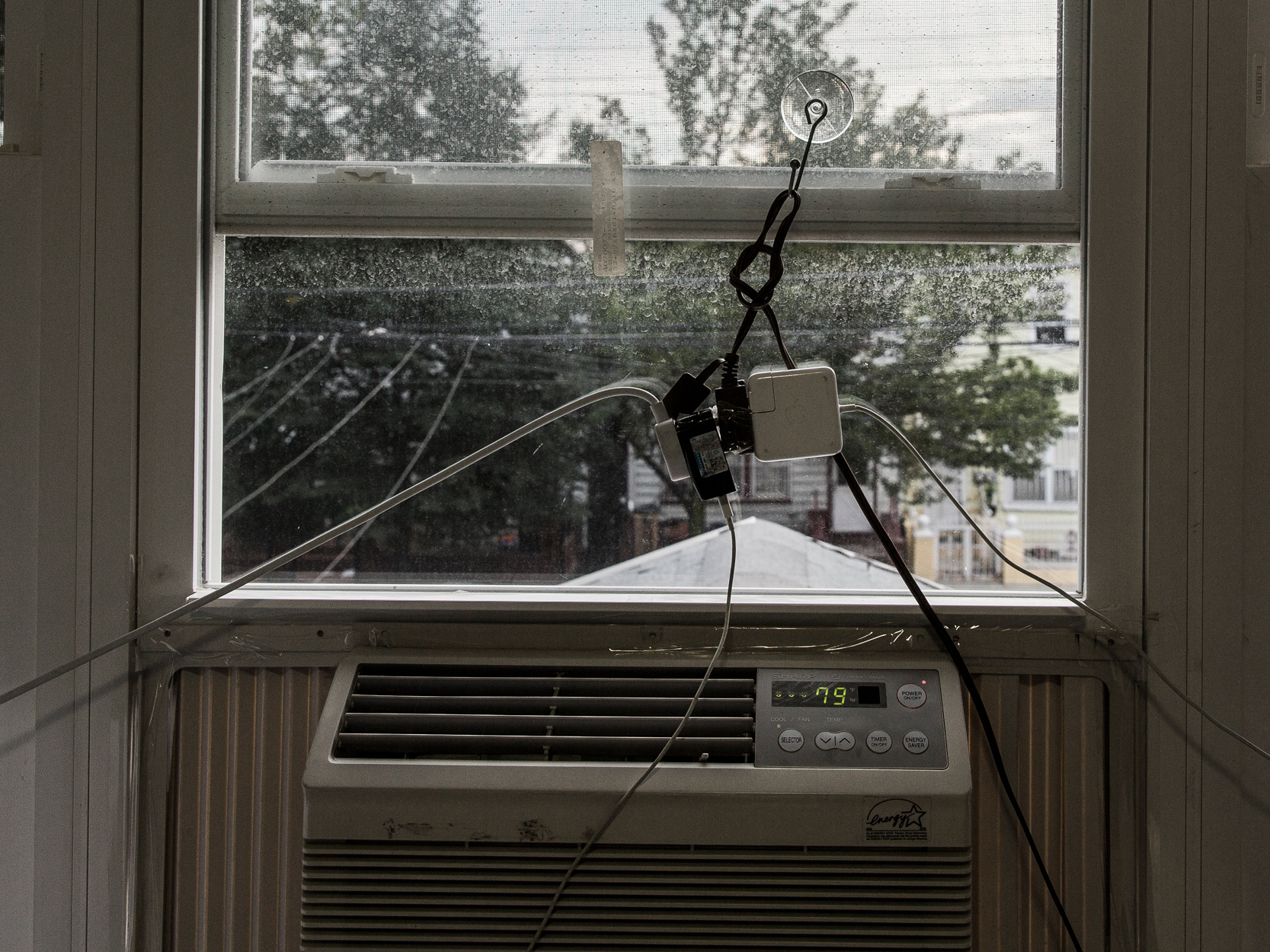

With the pressure mounting, Mr. Lu has taken a visiting scholar position in New York. The 43-year-old now spends most of his time hunched over his phone and laptop in a cramped, bare-walled apartment in Queens, battling to preserve his network from afar.

In doing so, he has thrown aside the practice of staying out of the spotlight that many say is part of his success.

“Before, when I wasn’t talking, they still detained my colleagues, still ransacked my office,” he says, while walking through Flushing Meadows park on a recent Saturday afternoon.

During a regular press briefing in April, China’s foreign ministry took the unusual step of mentioning Mr. Lu’s organization, Yirenping, by name, saying it was suspected of acting illegally and “will be punished”—a statement he has openly challenged. The foreign ministry and police have declined to respond to multiple requests for comment about authorities’ treatment of Yirenping.

Mr. Lu focuses on discrimination and other social issues that dovetail with the Communist Party’s principles, if not its practices. He has influenced government policy on labor and domestic abuse, and helped win millions of dollars in settlements for hepatitis-B carriers and other disadvantaged groups. He helped pioneer the use of stunt-based protests that have redefined Chinese activism in the social media age. State media have twice named him to lists of the country’s 10 most influential legal figures, though he isn’t a lawyer.

He has managed to keep his organization, Yirenping, running while authorities have taken down most other networks of activists.

“This is a man who has improved the lives of millions of people,” says Ira Belkin, an expert in Chinese law and civil society at New York University’s U.S.-Asia Law Center, where Mr. Lu is studying.

With the pressure mounting, Mr. Lu has taken a visiting scholar position in New York. The 43-year-old now spends most of his time hunched over his phone and laptop in a cramped, bare-walled apartment in Queens, battling to preserve his network from afar.

In doing so, he has thrown aside the practice of staying out of the spotlight that many say is part of his success.

“Before, when I wasn’t talking, they still detained my colleagues, still ransacked my office,” he says, while walking through Flushing Meadows park on a recent Saturday afternoon.

During a regular press briefing in April, China’s foreign ministry took the unusual step of mentioning Mr. Lu’s organization, Yirenping, by name, saying it was suspected of acting illegally and “will be punished”—a statement he has openly challenged. The foreign ministry and police have declined to respond to multiple requests for comment about authorities’ treatment of Yirenping.

Mr. Lu focuses on discrimination and other social issues that dovetail with the Communist Party’s principles, if not its practices. He has influenced government policy on labor and domestic abuse, and helped win millions of dollars in settlements for hepatitis-B carriers and other disadvantaged groups. He helped pioneer the use of stunt-based protests that have redefined Chinese activism in the social media age. State media have twice named him to lists of the country’s 10 most influential legal figures, though he isn’t a lawyer.

He has managed to keep his organization, Yirenping, running while authorities have taken down most other networks of activists.

“This is a man who has improved the lives of millions of people,” says Ira Belkin, an expert in Chinese law and civil society at New York University’s U.S.-Asia Law Center, where Mr. Lu is studying.

Past crackdowns against advocacy groups in China have been fed by fears of the role Western-funded nonprofits played in the protest movements that swept away autocratic regimes in the former Soviet Union, the Arab world and elsewhere. Under Mr. Xi, the rhetoric and vigilance against these “color revolutions”—so named because protesters often wore the same color clothing or accessories—has expanded into a vast, systematic campaign.

In the latest turn, scores of lawyers and activists known for confrontational tactics have been detained and arrested. The government enacted a new national security law in July that broadly defines threats to the state. It is also considering legislation that gives the police the power to supervise foreign nonprofit organizations and bans them from funding Chinese civic groups.

“The message from the government is, ‘Anything foreign, anything we don’t control, is potentially a threat to our national security’—and that’s a message that worries everybody,” says Tom Malinowski, assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights and labor in the U.S. The U.S. State Department, he says, is particularly concerned with the new laws, which civil society experts say would effectively strangle independent Chinese nonprofits.

Chinese authorities say the laws will benefit foreign groups by giving them a way to register legally in China as nonprofits—an option currently unavailable.

Mr. Lu says his group’s dependence on foreign support made it a target.

More than 80% of Yirenping’s funding comes from foreign sources, Mr. Lu says. The National Endowment for Democracy, which is funded by the U.S. Congress and has been linked to democratic movements in the former Soviet bloc, gave Yirenping $206,000 between 2007 and 2009, according to U.S. tax documents. The endowment declined to comment on more recent grant-giving. Mr. Lu wouldn’t comment about specific sources of overseas funding.

China’s Ministry of Public Security didn’t respond to requests for comment about investigations into Mr. Lu, Yirenping or others affiliated with the group.

Mr. Lu eschews large-scale protests and statements as too confrontational. Instead, he uses targeted lawsuits to push for incremental legal victories that, added up, produce change.

In 2007, Mr. Lu took aim at employment discrimination based on appearance, suing on behalf of a teacher who says she was fired after her school principal said her head was too large. A blog he encouraged the woman to write attracted media attention. After months of publicity on what became known as the “Big Head Girl” case, the education company that hired her settled the case, giving her 10,000 yuan (US$1,570) in compensation and a three-year contract that paid her to do nonprofit work full-time.

In an interview with state media, the education company’s general manager attributed the case to misunderstandings on both sides.

Mr. Lu’s willingness to settle cases has been controversial among activists who believe lawsuits should be fought to the end without consideration of financial rewards. But Mr. Lu says the outcomes are often better than relying on the uncertain court system, and settlements attract more plaintiffs.

In the latest turn, scores of lawyers and activists known for confrontational tactics have been detained and arrested. The government enacted a new national security law in July that broadly defines threats to the state. It is also considering legislation that gives the police the power to supervise foreign nonprofit organizations and bans them from funding Chinese civic groups.

“The message from the government is, ‘Anything foreign, anything we don’t control, is potentially a threat to our national security’—and that’s a message that worries everybody,” says Tom Malinowski, assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights and labor in the U.S. The U.S. State Department, he says, is particularly concerned with the new laws, which civil society experts say would effectively strangle independent Chinese nonprofits.

Chinese authorities say the laws will benefit foreign groups by giving them a way to register legally in China as nonprofits—an option currently unavailable.

Mr. Lu says his group’s dependence on foreign support made it a target.

More than 80% of Yirenping’s funding comes from foreign sources, Mr. Lu says. The National Endowment for Democracy, which is funded by the U.S. Congress and has been linked to democratic movements in the former Soviet bloc, gave Yirenping $206,000 between 2007 and 2009, according to U.S. tax documents. The endowment declined to comment on more recent grant-giving. Mr. Lu wouldn’t comment about specific sources of overseas funding.

China’s Ministry of Public Security didn’t respond to requests for comment about investigations into Mr. Lu, Yirenping or others affiliated with the group.

Mr. Lu eschews large-scale protests and statements as too confrontational. Instead, he uses targeted lawsuits to push for incremental legal victories that, added up, produce change.

In 2007, Mr. Lu took aim at employment discrimination based on appearance, suing on behalf of a teacher who says she was fired after her school principal said her head was too large. A blog he encouraged the woman to write attracted media attention. After months of publicity on what became known as the “Big Head Girl” case, the education company that hired her settled the case, giving her 10,000 yuan (US$1,570) in compensation and a three-year contract that paid her to do nonprofit work full-time.

In an interview with state media, the education company’s general manager attributed the case to misunderstandings on both sides.

Mr. Lu’s willingness to settle cases has been controversial among activists who believe lawsuits should be fought to the end without consideration of financial rewards. But Mr. Lu says the outcomes are often better than relying on the uncertain court system, and settlements attract more plaintiffs.

“You can only defend your rights by using the law, and you only win a case by influencing public opinion. There is no other way to do it,” Mr. Lu says.

Unlike many groups that tend to be centered on a single personality, and hence easily shut down, Mr. Lu encourages employees to start new organizations, thereby broadening his network.

Stunt protests spread via social media have amplified that influence. “Occupy Men’s Toilet”—a 2012 campaign led by the women’s rights activist Ms. Li, in which young women briefly took over public men’s bathrooms—led to promises from local governments to add more facilities for women.

At a training session for Chinese nonprofit founders in Hong Kong in 2013, participants fell to arguing while Mr. Lu stayed out of the fray, according to an organizer. “You’re in a room full of NGO leaders, all of them lawyers and all of them shouting, trying to outdo each other and be the smartest person in the room,” the organizer says. “But Lu Jun stands off to the side, listening intently to people and sucking up information.”

The son of a policewoman and a former People’s Liberation Army tank driver, Mr. Lu stayed out of politics growing up in the central city of Zhengzhou. When his high-school classmates marched in support of the Tiananmen Square democracy protests in Beijing in 1989, Mr. Lu says he stayed in his dorm, unsure what to believe.

As a chemistry major at Zhongnan University, his views became more skeptical after he found a book in the library that detailed the mass starvation caused by Mao Zedong’s collectivist policies in the 1950s.

“I felt I’d been lied to all my life,” he says. “It taught me that the government needs to be supervised. Without supervision, it will make a lot of mistakes.”

Road to activism

A medical condition led Mr. Lu to activism. Toward the end of college, he was diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B, a disease that affects the liver. Searching the Internet for hepatitis-B treatments in 2003 led him to an online forum for carriers of the virus. According to the government, about 10% of China’s population is infected with the hepatitis-B virus, which is controllable with a vaccine. But rules which dated to an outbreak of the more infectious hepatitis-A virus in Shanghai in 1988 banned hepatitis carriers from working in jobs ranging from food service to education.

He launched an online petition in 2004 for the laws to be changed. The government responded, saying it would re-examine the laws, and eventually removed hepatitis B from health checks for the civil service. It was the first of more than a dozen laws and regulations Mr. Lu would have a hand in shaping, including laws on food safety, employment and mental health.

Encouraged, Mr. Lu set up Yirenping—a combination of the characters for “public interest,” “kindness” and “equality”—in a small office in Zhengzhou in 2006. He opened a larger office in Beijing a few months later to concentrate full time on antidiscrimination work.

Unlike many groups that tend to be centered on a single personality, and hence easily shut down, Mr. Lu encourages employees to start new organizations, thereby broadening his network.

Stunt protests spread via social media have amplified that influence. “Occupy Men’s Toilet”—a 2012 campaign led by the women’s rights activist Ms. Li, in which young women briefly took over public men’s bathrooms—led to promises from local governments to add more facilities for women.

At a training session for Chinese nonprofit founders in Hong Kong in 2013, participants fell to arguing while Mr. Lu stayed out of the fray, according to an organizer. “You’re in a room full of NGO leaders, all of them lawyers and all of them shouting, trying to outdo each other and be the smartest person in the room,” the organizer says. “But Lu Jun stands off to the side, listening intently to people and sucking up information.”

The son of a policewoman and a former People’s Liberation Army tank driver, Mr. Lu stayed out of politics growing up in the central city of Zhengzhou. When his high-school classmates marched in support of the Tiananmen Square democracy protests in Beijing in 1989, Mr. Lu says he stayed in his dorm, unsure what to believe.

As a chemistry major at Zhongnan University, his views became more skeptical after he found a book in the library that detailed the mass starvation caused by Mao Zedong’s collectivist policies in the 1950s.

“I felt I’d been lied to all my life,” he says. “It taught me that the government needs to be supervised. Without supervision, it will make a lot of mistakes.”

Road to activism

A medical condition led Mr. Lu to activism. Toward the end of college, he was diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B, a disease that affects the liver. Searching the Internet for hepatitis-B treatments in 2003 led him to an online forum for carriers of the virus. According to the government, about 10% of China’s population is infected with the hepatitis-B virus, which is controllable with a vaccine. But rules which dated to an outbreak of the more infectious hepatitis-A virus in Shanghai in 1988 banned hepatitis carriers from working in jobs ranging from food service to education.

He launched an online petition in 2004 for the laws to be changed. The government responded, saying it would re-examine the laws, and eventually removed hepatitis B from health checks for the civil service. It was the first of more than a dozen laws and regulations Mr. Lu would have a hand in shaping, including laws on food safety, employment and mental health.

Encouraged, Mr. Lu set up Yirenping—a combination of the characters for “public interest,” “kindness” and “equality”—in a small office in Zhengzhou in 2006. He opened a larger office in Beijing a few months later to concentrate full time on antidiscrimination work.

Hong Kong University law professor Fu Hualing credits the group with effectively eliminating legal discrimination against hepatitis-B carriers by 2010. Mr. Lu and his protégés have since expanded their targets to include discrimination against the disabled, women, and gay, lesbian and transgender people.

Though the protest stunts and other publicity occasionally brought pressure, Mr. Lu says, his network overall maintained good relations with police.

He says the situation began to change in May last year. A lawyer who served as the legal representative of Zhengzhou Yirenping was detained while attempting to defend clients unrelated to the group who had been apprehended after meeting to discuss the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown. The next month, Zhengzhou Yirenping was served with a questionnaire about its activities and funding sources, part of a nationwide investigation into nonprofits ordered by Mr. Xi’s newly established National Security Commission. Soon after, police froze the group’s bank accounts and raided its office, according to Mr. Lu and other Yirenping employees.

Though the lawyer was later released, the detention and harassment of others connected to Yirenping followed. After the March detention of the five female activists, police churned through the office of Beijing Yirenping and emptied out the safe where it kept grant documents and labor contracts, according to Mr. Lu.

Though the protest stunts and other publicity occasionally brought pressure, Mr. Lu says, his network overall maintained good relations with police.

He says the situation began to change in May last year. A lawyer who served as the legal representative of Zhengzhou Yirenping was detained while attempting to defend clients unrelated to the group who had been apprehended after meeting to discuss the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown. The next month, Zhengzhou Yirenping was served with a questionnaire about its activities and funding sources, part of a nationwide investigation into nonprofits ordered by Mr. Xi’s newly established National Security Commission. Soon after, police froze the group’s bank accounts and raided its office, according to Mr. Lu and other Yirenping employees.

Though the lawyer was later released, the detention and harassment of others connected to Yirenping followed. After the March detention of the five female activists, police churned through the office of Beijing Yirenping and emptied out the safe where it kept grant documents and labor contracts, according to Mr. Lu.

One of the women, Wu Rongrong, says that after her release on bail, police called her in for an eight-hour interrogation. Ms. Wu says police told her their target was Yirenping and asked her for information about Mr. Lu. “They got very angry when I didn’t tell them what they wanted to hear,” she says.

Police in Beijing, Hangzhou and Zhengzhou didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Already a visiting scholar at Yale University, Mr. Lu decided to stay in the U.S., moving to New York University in August. From there, Mr. Lu has worked with lawyers in China to challenge the police raid on his office and pressure prosecutors to drop charges against the women activists.

The efforts have paid off, at least to a certain extent. All Yirenping staff members detained so far have been released on bail—a result he attributes to legal and media pressure. Meanwhile, Beijing has faced increasing international pressure to clear the women activists of wrongdoing.

That has left Mr. Lu optimistic that independent civic groups will survive in China in the long run. Eating a lunch of store-bought macaroni and homemade stir-fried tomatoes in his apartment while his infant daughter crawled at his feet, Mr. Lu says he plans to return to China—though not in the near future. “They’re still detaining people left and right,” he said. “It’s still too dangerous to go back now.”

by Josh Chin

Police in Beijing, Hangzhou and Zhengzhou didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Already a visiting scholar at Yale University, Mr. Lu decided to stay in the U.S., moving to New York University in August. From there, Mr. Lu has worked with lawyers in China to challenge the police raid on his office and pressure prosecutors to drop charges against the women activists.

The efforts have paid off, at least to a certain extent. All Yirenping staff members detained so far have been released on bail—a result he attributes to legal and media pressure. Meanwhile, Beijing has faced increasing international pressure to clear the women activists of wrongdoing.

That has left Mr. Lu optimistic that independent civic groups will survive in China in the long run. Eating a lunch of store-bought macaroni and homemade stir-fried tomatoes in his apartment while his infant daughter crawled at his feet, Mr. Lu says he plans to return to China—though not in the near future. “They’re still detaining people left and right,” he said. “It’s still too dangerous to go back now.”

by Josh Chin