On this part of the eastern front, Russia is still on the attack

for the Washington Post

By Francesca Ebel and Kamila Hrabchuk - published on June 27, 2023

KREMINNA FOREST, Ukraine — For five days, the attacking Russians threw everything they had at the Ukrainian brigade defending a patch of forest here on the eastern front — mortar, artillery, flamethrowers and tank fire — mowing down whatever stood in their way. By the sixth day, bodies littered the smoldering terrain. Only a scorched field and blackened tree stumps remained.

“We had to retreat,” said an infantryman, who goes by the call sign “Master,” describing the battle earlier this month. “It was very challenging for the infantry to hold the front, because we were being pushed very hard by the Russians, without adequate artillery cover.”

The forest, just west of Kreminna, a Russian-occupied town in Ukraine’s Luhansk region, is now an epicenter of some of the war’s fiercest fighting. But unlike elsewhere on the eastern and southern fronts, where Ukraine has mounted a long-anticipated counteroffensive, the fighting here is being driven by Russia — in its latest push to seize the entire eastern Donbas region.

“We had to retreat,” said an infantryman, who goes by the call sign “Master,” describing the battle earlier this month. “It was very challenging for the infantry to hold the front, because we were being pushed very hard by the Russians, without adequate artillery cover.”

The forest, just west of Kreminna, a Russian-occupied town in Ukraine’s Luhansk region, is now an epicenter of some of the war’s fiercest fighting. But unlike elsewhere on the eastern and southern fronts, where Ukraine has mounted a long-anticipated counteroffensive, the fighting here is being driven by Russia — in its latest push to seize the entire eastern Donbas region.

An armored vehicle is hidden in the Kreminna forest

According to Ukrainian soldiers, Moscow has bolstered its eastern forces and intensified its attacks, aiming to recapture towns and cities that Ukraine liberated in the fall.

Master, who was recuperating from the battle in Yampil, a front-line village on the outskirts of the forest in eastern Ukraine, said that as a result of the attack, the Russians had advanced roughly 300 to 400 meters — up to a quarter of a mile — on the north side of the forest. “They are certainly attacking more intensely and advancing in this direction,” he said. The Washington Post is not identifying Master or other soldiers because of security concerns.

Unlike in Zaporizhzhia, for instance, where the Russians are dug into heavily fortified defenses and the Ukrainians are trying to advance, in the Kreminna forest, the side that is attacking or defending can vary day-to-day or even hour by hour.

A Ukrainian platoon commander, who goes by the call sign “Hephaestus,” said Russia’s operations in the east had “dramatically increased.” Within just one 24-hour stretch this week, he said, there were six attempted attacks on his brigade’s sector.

Ukrainian Army Medics on duty in the Kreminna forest

“They are losing the initiative in the south and near Bakhmut,” Hephaestus said. “Therefore, they need to give something to Russian society at a political level to show they have some ambition and advantage. The Donetsk and Luhansk regions have always been a priority for Russia.”

A British intelligence memo on Sunday reported that Russian forces had made a “significant effort” to launch an attack on the Serebryanka forest near Kreminna, an adjoining forest to the southeast of the Kreminna wood.

“This probably reflects continued Russian senior leadership orders to go on the offensive whenever possible,” the memo stated. “Russia has made some small gains, but Ukrainian forces have prevented a breakthrough.”

As Russian forces struggle to advance, they continue to pummel civilian targets in the east. Tuesday night, in the city of Kramatorsk, an Iskander ballistic missile slammed through the roof of a popular restaurant. At least 11 people were killed, including three children, Ukrainian authorities said, and at least 61 were injured, including an 8-month-old.

Soldiers of a mortar unit of the Bureviy National Guard brigade, from left: Maly, junior sergeant; Sasha, division engineer; Bohdan, unit commander; and Vitaly, radio operator of the unit

Soldiers of a mortar unit of the Bureviy National Guard brigade, from left: Maly, junior sergeant; Sasha, division engineer; Bohdan, unit commander; and Vitaly, radio operator of the unit

The Kreminna forest is now one of the most dangerous spots on the front line. Winding toward the forest through the moonscape of what used to be people’s homes, there are few signs of life. A lone soldier on a bicycle. A rusting basketball hoop. “People live here,” scrawled across the gate of a shrapnel-riddled house. The gargantuan task Ukraine faces in reclaiming its stolen territory is quickly apparent.

On Saturday, Post journalists accompanied the platoon commander Hephaestus as he drove to fallback positions in the forest. A voice crackled on the walkie-talkie. “Up ahead, there’s a mortar unit — be aware, they could fire at any time.” The road through the forest is unpredictable and constantly hit by mortar rounds and artillery. Warrens of trenches run through the woods, while armored vehicles and rocket launchers are tucked away in the undergrowth.

“The concentration of the enemy is now much higher in the forests of Kreminna than in any other areas of the front,” Hephaestus explained. “It is connected with the landscape. Thanks to the dense forests, it is easy enough for the enemy to hide a large number of troops and equipment.”

“Every movement should be gradual,” he added. “The priority for us is every human life. If we use them unplanned and irrationally, there will be unjustifiably immense sacrifices.”

One of the artillery units of the Ukrainian air assault forces at their firing positions on the eastern front

A group of medics stationed at an evacuation point in the forest said the situation varied from week to week but had become noticeably harder in recent days. In previous weeks, they were rotated every 10 days, but now, they are being rotated every two due to the uptick in fighting.

“Two days ago, we were working throughout the night, I lost track of how many calls there were,” said a 25-year-old medic known as “Priest.” He played a recording he had made on his phone of an assault near their position one night that week: a stomach-twisting soundtrack of relentless bombardments that lasted for hours.

Priest estimated that casualties for the Lyman region, which includes the Kreminna forest, has increased by 10 times. In his particular brigade, he said, there had been about 70 casualties in two days.

A web of threats lurk in the woods. The terrain itself — a mishmash of thick pine forests, swamps, lakes and hills — is difficult and hinders the rapid advance of assault units. Mines, drones and smoke from the near-constant fires that rage from the shelling make the territory even more lethal. Then there are roving reconnaissance groups.

“Two days ago, we were working throughout the night, I lost track of how many calls there were,” said a 25-year-old medic known as “Priest.” He played a recording he had made on his phone of an assault near their position one night that week: a stomach-twisting soundtrack of relentless bombardments that lasted for hours.

Priest estimated that casualties for the Lyman region, which includes the Kreminna forest, has increased by 10 times. In his particular brigade, he said, there had been about 70 casualties in two days.

A web of threats lurk in the woods. The terrain itself — a mishmash of thick pine forests, swamps, lakes and hills — is difficult and hinders the rapid advance of assault units. Mines, drones and smoke from the near-constant fires that rage from the shelling make the territory even more lethal. Then there are roving reconnaissance groups.

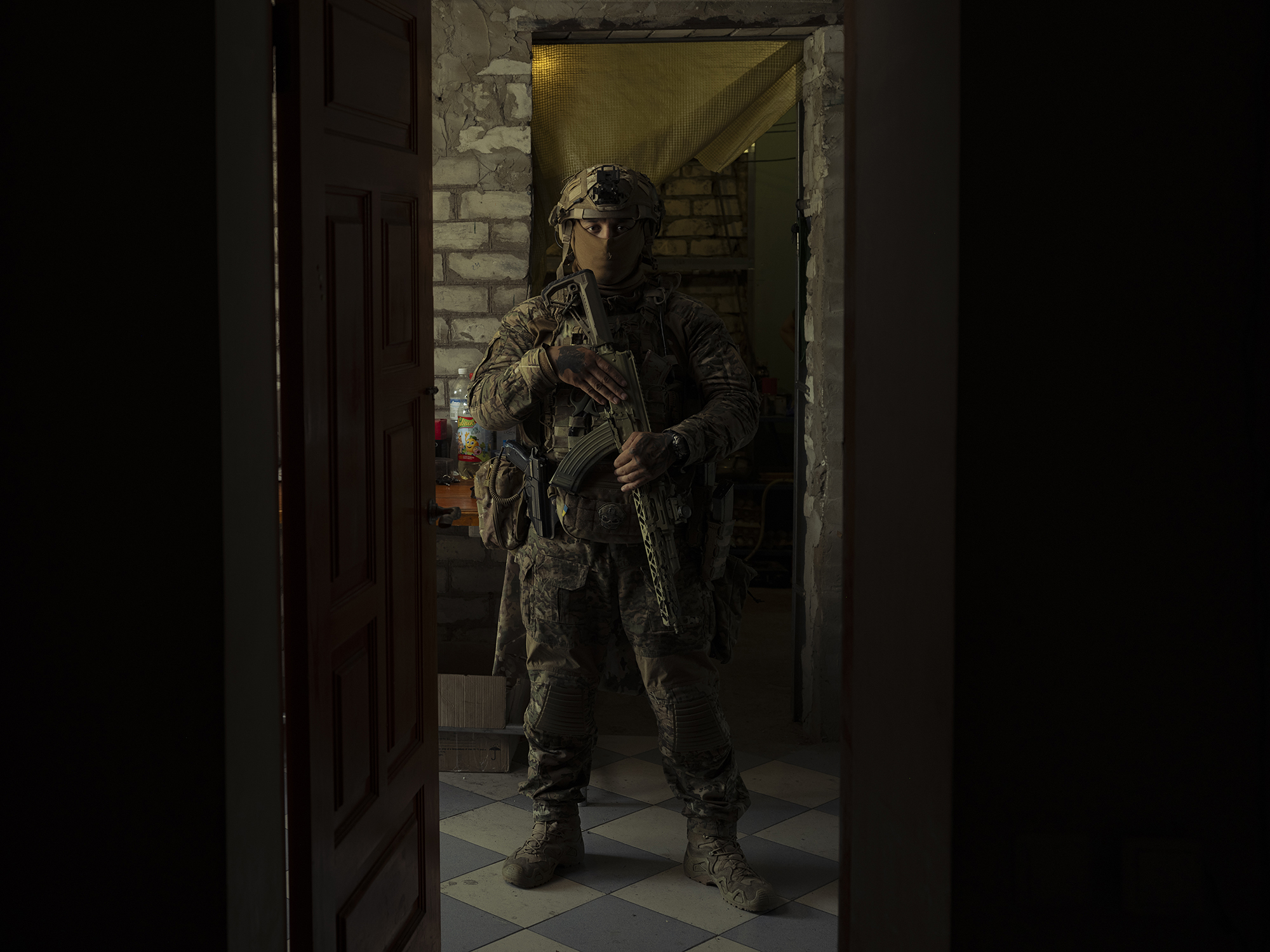

Ukrainian National Guardsman cleaning his weapon outside of Kreminna forest

One night last week, Hephaestus carefully led his unit on a mission to find weak spots in enemy lines. As the unit slowly made its way in the dark through the dense woodland, cutting through thickets of nettles and foxgloves, they could smell the burning pines. The Russians were bombing the woods again with flamethrowers, a tactic used to both obscure the view of reconnaissance drones and to smoke out the locations of Ukrainian positions and equipment.

Suddenly, the lead scouts signaled that they had spotted movement up ahead. The unit stopped. Looking through night-vision goggles, they identified the silhouettes of a Russian reconnaissance unit further up in the woods, roughly 10 meters away. The unit opened fire. A few minutes later, all the Russians lay dead.

“This is the forest,” said Hephaestus with a shrug, adding that it is common to come face-to-face with enemy units in the woods. “Sometimes we are able to catch the enemy by surprise … if you stand still, you can hear a crunch, a whisper — especially at night when it’s quiet.”

Suddenly, the lead scouts signaled that they had spotted movement up ahead. The unit stopped. Looking through night-vision goggles, they identified the silhouettes of a Russian reconnaissance unit further up in the woods, roughly 10 meters away. The unit opened fire. A few minutes later, all the Russians lay dead.

“This is the forest,” said Hephaestus with a shrug, adding that it is common to come face-to-face with enemy units in the woods. “Sometimes we are able to catch the enemy by surprise … if you stand still, you can hear a crunch, a whisper — especially at night when it’s quiet.”

A 27-year-old commander of one of the units of the Bureviy National Guard brigade, who goes by the call-sign "Hephaestus," poses for a portrait in the Kreminna forest

A 27-year-old commander of one of the units of the Bureviy National Guard brigade, who goes by the call-sign "Hephaestus," poses for a portrait in the Kreminna forest

Sometimes the Russians wear Ukrainian uniforms taken from the soldiers they killed or captured, to try to infiltrate Ukrainian lines. They can be a large, elite fighting group or a handful of inexperienced recruits who were sent directly to the front lines.

When a Post reporting team visited an artillery position on the Serebryanka flank Saturday morning, active hostilities were underway. The percussive booms of shells and whistle of incoming fire cut through the otherwise eerie silence. Five young, exhausted soldiers emerged, blinking into the sunlight from their shelter, and hurried to their positions, where they prepared to fire several rounds from an L119 howitzer gun.

Their 40-year-old commanding officer, who goes by the call sign “Scythian,” has been stationed in the area for the past six months and said that the level of shelling from the Russian side had increased in recent weeks. He said the Russians had also amassed armored vehicles and tanks that had not been observed before. “That the enemy is building up forces in this area is clear,” he said.

When a Post reporting team visited an artillery position on the Serebryanka flank Saturday morning, active hostilities were underway. The percussive booms of shells and whistle of incoming fire cut through the otherwise eerie silence. Five young, exhausted soldiers emerged, blinking into the sunlight from their shelter, and hurried to their positions, where they prepared to fire several rounds from an L119 howitzer gun.

Their 40-year-old commanding officer, who goes by the call sign “Scythian,” has been stationed in the area for the past six months and said that the level of shelling from the Russian side had increased in recent weeks. He said the Russians had also amassed armored vehicles and tanks that had not been observed before. “That the enemy is building up forces in this area is clear,” he said.

Soldiers from the Bureviy National Guard brigade are putting on colors of the day before heading out on a task in the Kreminna forest

An artillery commander of the National Guard, who goes by the call sign “Brave,” said that the battle lines in the forest were constantly shifting and rarely stable.

“The enemy, like us, retreats in places and conducts counteroffensive actions; they break through certain positions and lines. Like us, in some places, they advance and elsewhere they sacrifice some positions,” he said.

Brave said that such attacks can happen up to 10 times a day. “When there is a tip from reconnaissance units that perhaps an infantry breakthrough is being prepared or a concentration is taking place in the forest, we begin to work,” he said.