The Rolling Hospital

A train picks up wounded soldiers from the Ukrainian front every day. Also traveling with them: the unwavering will to keep living.

for Die Zeit

The Secret Channel Russia and Ukraine Use to Trade Prisoners of War

Peace talks are fraught on the eve of the Putin-Trump summit, yet the two countries have managed to trade more than 10,000 troops, something virtually unheard of in modern warfare

for the WSJ

The Synagogue Massacre That Never Happened

They were two troubled young men, hurtling toward an atrocity. One was the grandson of a Holocaust survivor.

Article by John Leland

March 24, 2025

Matthew Mahrer as a boy wrote a 25-page book about his grandfather’s experiences as a prisoner in a Nazi internment camp.

Christopher Brown did favors for the Orthodox rabbi across the street, who needed someone to turn on electrical devices during the Sabbath or Jewish holidays.

In November 2022, they were both in free fall. Christopher Brown, then 21, posted on Twitter that he wanted to “shoot up a synagogue and die.”

Matthew Mahrer helped him get the gun.

They were drunk or high, heading into New York City with a Glock 9-millimeter pistol, an extended magazine and 19 bullets. When they were arrested in Pennsylvania Station that night, it rattled a Jewish community that was still on edge from the massacre of 11 people at a Pittsburgh synagogue four years earlier.

Their arrest was a chilling story — an “antisemitic sicko” bent on mass murder — made more sensational by the revelation that his accomplice was Jewish.

“There were 19 bullets in that ammo clip,” said Glenn Richter, who attended a synagogue near the Mahrers. “Had they decided to go around the corner and go into the synagogue, I and others could have been among those 19 casualties.”

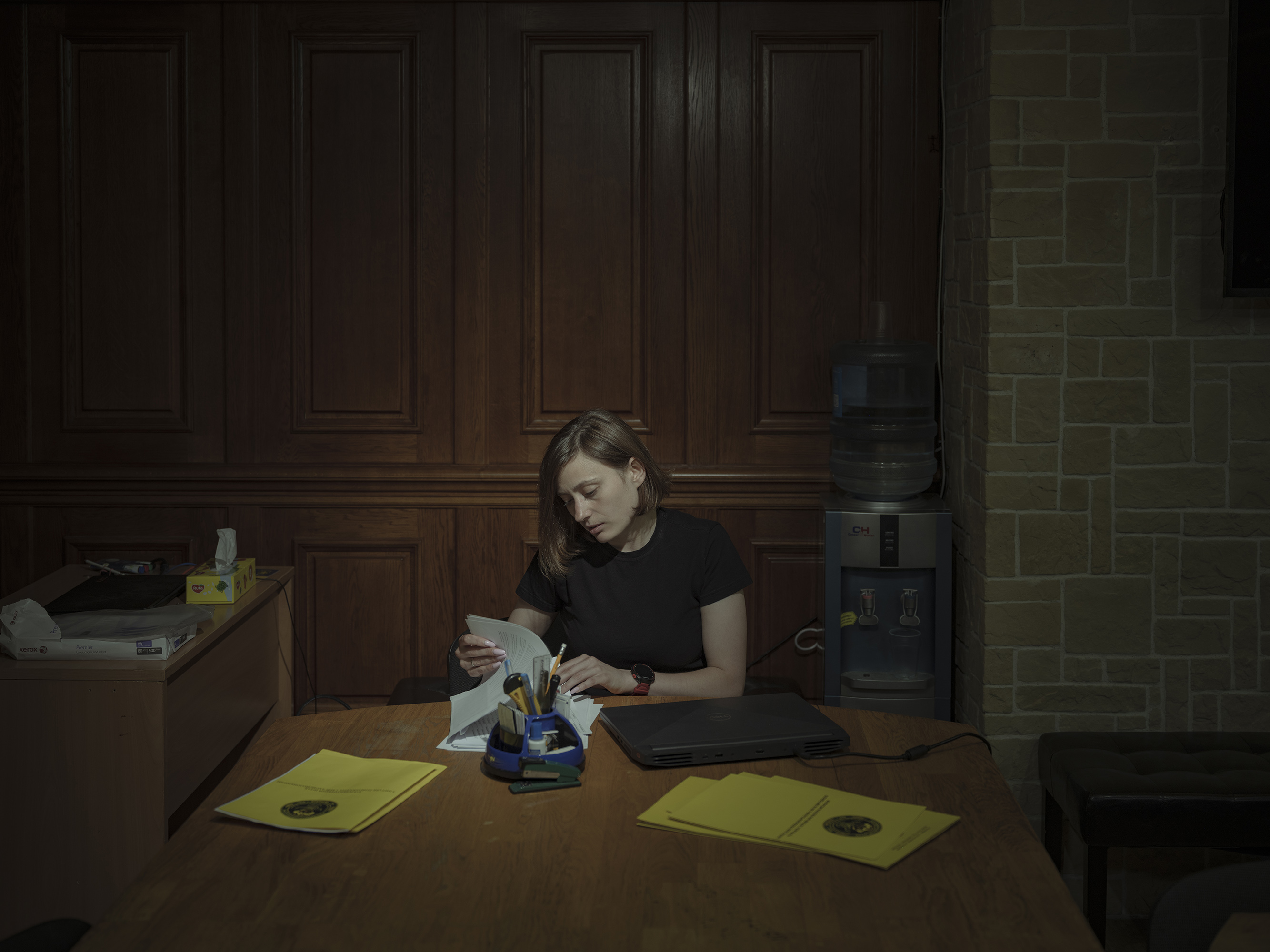

Glenn Richter, a Jewish community leader who led an opposition to Mahrer, in the Congregation Ohab Zedek Synagogue at 120 W 95th St. "It’s logical to conclude that this was the intended target", Mr.Richter said about the foiled attack. The temple is located a block away from the Mahrer residence and Mr.Richter thinks Matthew Mahrer and Christopher Brown could have attacked this particular synagogue.

Underneath the fear were the more complicated stories of two young men living with mental illness, thrown together by institutions that left them more troubled than when they went in.

Bullied as children, medicated from a young age, Christopher Brown and Matthew Mahrer followed a line of failings, personal and institutional, to the brink of atrocity.

A Jewish Boyhood, Interrupted

Fifteen minutes into my first conversation with Matthew Mahrer, he blew up at his parents and stalked out of the apartment, apologizing on the way out.

When he returned soon afterward, calmed, it was as if the blowup had never happened.

“Have you ever heard of post-traumatic growth theory?” he asked.

We were in his grandmother’s apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side in early January, three weeks before he was scheduled to be sentenced for criminal possession of a weapon. Prominently displayed was a framed fabric gold star with the word “Jude,” from the camp where his grandfather was interned as a teenager.

Matthew Mahrer in the bedroom at his parents’ apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

Matthew Mahrer in the bedroom at his parents’ apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.At 24, out on bail, Matthew displayed a quick intelligence and low social awareness. He wore his hair in loose curls that partially hid his eyes, and he spoke in unfiltered gushes.

His parents, retreating to the room’s periphery to avoid upsetting him, wore the weight of the years on their faces.

Matthew’s troubles began at age 3, when he couldn’t sit still at preschool, and his parents had to pull him out. The diagnosis then was sensory integration disorder — “because at that age they’re too young to be diagnosed with anything else,” his mother, Susan, said. From then on, his life was a roller coaster of different diagnoses, different therapies and — starting at age 5 — more and more medications.

When he was in grade school, Matthew Mahrer composed a 25-page book about his grandfather’s time in a Nazi internment camp. Credit...Sasha Maslov for The New York Times

He was assessed as having A.D.H.D., then later pervasive developmental disorder, anxiety disorder, PTSD and, in high school, autism spectrum disorder. Twice he was hospitalized for psychiatric care, once because he was cutting himself. “That was his childhood,” his mother said.

He was also bright enough to test into a gifted and talented program in elementary school.

Social skills eluded him. He was the squirmy kid, bullied, unable to sit still. Classmates he thought were his friends beat him up or humiliated him.

By high school he was failing, disappearing in the middle of the school day. His parents began looking for residential schools that provided therapeutic environments.

It was at one of these programs that he met Christopher Brown.

The Making of a Child Neo-Nazi

The Mahrers entered the mental health care system as a solid family unit with a lot of resources. Matthew’s father taught in the public schools. His mother had a background in early childhood education and ran a small business. They had experience in navigating bureaucracies and excellent health insurance.

Christopher Brown’s family, in Stony Brook, on Long Island, had none of these.

“We didn’t have electricity in half of our house, we didn’t have any running water, the heat wasn’t working,” his younger sister, Kayla Brown, now 22, said. “We were very neglected. C.P.S.” — Child Protective Services — “was involved in our life a lot.”

In interviews with Christopher, his parents, an aunt and his sister, each labeled different family members as abusive or neglectful, but all said that a lot of that fell on Christopher.

In the visiting room at Clinton Correctional Facility in January, near the Canadian border, the man who met me was nothing like his numerous toxic tweets. Now 23, he wore a kufi skullcap, signifying his jail-cell conversion to Islam, and spoke softly and thoughtfully about the actions and bigotry that landed him there.

“I’m sorry to Matthew for ruining his life,” he said.

As a child, Christopher was, like Matthew, smart, socially challenged and bullied by classmates. He’d cling to his mother or close himself off in his room and play video games, refusing to bathe or go to school.

Home life was volatile, both of his parents said. His mother, who has Crohn’s disease, moved out when he was around 9; his father left a year later, leaving him with his grandmother and an aunt. Christopher would ask, “Why did you even bother having me?” his mother, KerryAnn Brown, said.

His sister thinks he started to unravel when their mother left.

“I just remember he was more angry,” she said. “I don’t want to say he would get violent, but he would have tantrums a lot, which he never had before. He almost changed into a completely different person.”

Still, Shalom Ber Cohen, the rabbi whom Christopher helped on the Sabbath, remembered him as a pleasant child living in a troubled home. Asked about later events, Rabbi Cohen said, “It’s scary to think it’s the same boy.”

Around the time that his parents left, Christopher developed compulsive blinking and other tics that led the school to send him for psychiatric evaluation. The diagnosis was schizophrenia.

Like Matthew, he received therapy and medications, which he resisted taking, to the extent that his grandmother would make him open his mouth to show that he had swallowed his pills.

He, too, started skipping school, finding refuge in the computer. At age 11 or 12 he discovered Facebook and, with it, neo-Nazi discussion groups. “What attracted me to them was the sense of community, camaraderie, and a sense of purpose,” he wrote in an email from prison. Suddenly, he was part of a crowd that not only welcomed him but also told him the problem was not him but other people.

He never met any of them off-line, he said. But in a flat, affectless tone, he said, “They corrupted my malleable mind.”

When he was 15, workers from Child Protective Services saw the state of his grandmother’s house and removed him to the first of several group homes.

Carolyn Mahrer, Matthew Mahrer's grandmother at their family residence on the Upper West side of Manhattan

Carolyn Mahrer, Matthew Mahrer's grandmother at their family residence on the Upper West side of Manhattan‘Why He Snapped’

The two boys met at St. Christopher’s, a home in Westchester County for students with intellectual and emotional disabilities.

If the Mahrers thought the school would help Matthew, they quickly learned otherwise.

“There was a lot of verbal and physical abuse and students attacking students and staff inflicting rough treatment on the children,” his father, Michael, said. (The home filed for bankruptcy protection last year, after dozens of lawsuits were filed under the state’s Child Victims Act, alleging child abuse.)

Many of the students had severe intellectual disabilities or had been sent there after being arrested.

“We thought we were sending him to a treatment center,” Matthew’s mother, Susan, said. “He got PTSD from it. And it formed his outlook, in a sense. This was his peer group.”

Paired as roommates, Matthew and Christopher initially clashed. “We hated each other LOL,” Matthew wrote in an email from prison.

Christopher thought Matthew was “noisy.” Matthew objected to Christopher’s racism. Christopher knew Matthew was Jewish.

But they would talk late into the night, united by boredom and a shared interest in video games. Sometimes Christopher mentioned suicide. Neither saw the world as a benign, friendly place.

Matthew says now that he’d viewed his roommate’s neo-Nazism as a reaction to trauma and rejection. These were feelings he knew well, he said.

Matthew, in turn, was drawn to the criminal types at the school, for similar reasons. He had previously explored gang culture only vicariously, through hyper-gritty drill rap. He was tired of being “a Jewish kid from the Upper West Side,” he said, and wanted to belong to something bigger than himself.

After graduation from St. Christopher’s, Matthew returned home in early 2020, at age 19.

Moving back with his parents meant adjusting to new rules. Almost immediately, Covid hit, and New Yorkers were told to stay at home to avoid spreading the virus. This was especially important in families like Matthew’s, with his grandparents living upstairs. But it was too much for Matthew, who would frequently bolt from the house to wander the neighborhood.

After a 2 a.m. confrontation with his father, at the height of Covid’s first wave, Matthew went to a homeless shelter in the Bronx. His first week there, he said, he watched a man die of an overdose in a bed near his. He would remain homeless for 10 months.

Whatever supports his parents had arranged for him were now gone. The city was in an acute mental health crisis, with therapists too overwhelmed to take new patients. “I was literally begging for therapy, and all I was ever getting was meds,” Matthew said. He started getting into fights, getting kicked out of one shelter after another.

“I felt like such a monster,” his mother said. “Like, my kid was always welcome to come home. He just needed to agree to be safe. He jumped from being exposed to young people with problems to now being exposed to adults with problems. And with bigger problems.”

Susan and Michael Mahrer on the balcony of their apartment. Their Jewish son had been made “a poster boy of antisemitism and neo-Nazism,” Ms. Mahrer said.

Susan and Michael Mahrer on the balcony of their apartment. Their Jewish son had been made “a poster boy of antisemitism and neo-Nazism,” Ms. Mahrer said. After one too many fights in the shelters, in January 2021 Matthew finally returned home.

Christopher, who by this time had also graduated from St. Christopher’s, moved to another group home.

He began posting threats against Jews and others on social media, invoking Brenton Tarrant, who in 2019 fatally shot 51 people at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand. In December 2021, Christopher tweeted, “I’m about to make Tarrant look like a moderate.”

Researchers who study extremist violence struggle to tell which people who post malevolent threats online are likely to go on to actual deeds. They look for concrete steps, like a specific attack plan or a written manifesto. “The vast majority” of people posting such threats never act on them, said John Horgan, a professor of global studies and psychology at Georgia State University, who studies radicalization and violent extremism. Often, he said, the only way to tell the talkers from the doers is after the fact.

Christopher and Matthew would talk occasionally by phone or text, sometimes mentioning guns: Could Matthew, who had boasted about having gang connections, get him a revolver? Christopher told me he wanted to play Russian roulette, because he wanted to die, but he did not want the certainty that this particular squeeze of the trigger would be the one.

In August 2022, Christopher turned 21 and aged out of his last group home. He had no money, no therapy and only a few doses of his medication. When he returned to his mother’s house, he had not lived outside an institution since he was 15.

His mother was now living on disability insurance at the far end of Long Island, with a man Christopher and his sister both described as abusive. The boyfriend, who died in January, forced Christopher to drink alcohol and would not let him sleep, Christopher said.

Christopher unraveled quickly.

“He was fine for a while,” Kayla Brown said. “But then, as the abuse from my mother’s boyfriend started getting worse, that’s when he started to become more argumentative or just more paranoid.”

She added: “If people knew what was going on in our life at the time, they would understand why he snapped.”

Shortly after Christopher moved into his mother’s home, the county sheriff’s office served her boyfriend with an extreme risk protection order, sometimes called a red flag notice, barring him from buying or owning a firearm. While officers searched the house, they photographed Christopher’s room, where he had a flag with a swastika and another with a Nazi SS insignia.

Recalling this period from prison two years later, Christopher said he was depressed and suicidal, disoriented from alcohol and a lack of sleep. On the chat app Discord in late October 2022, three weeks before his arrest, he mentioned a “plan” involving a synagogue, debating whether he should do it on his own or “join the Nazi organization.” Either way, he said, “I’m not living to see my next birthday.”

The same day he contacted Matthew by Snapchat about getting a gun, saying he needed it because some teenagers were threatening him and his family, Matthew said. Matthew, in turn, contacted a man he knew named Jamil Hakime, who worked at the Administration for Children’s Services. Hakime would eventually drive Matthew and Christopher to Pennsylvania and sell them a gun he kept in his house in the Poconos.

Christopher’s past threats had never moved beyond venomous talk for his social media followers. Now he seemed to be taking action.

Sleep-deprived and often drunk, he was posting constantly on Twitter, venting about Jews, women, gay people, any group that caught his ire. One tweet threatened, “I want all Irish out of my country by the time the sun rises or there will be consequences.”

Looking back, Christopher said that his tweets were provocations meant to garner likes, and that he did not plan to hurt anyone other than himself. But on Nov. 17 he arranged with Matthew to get the gun — not a revolver, but a Glock 9 millimeter with an extended magazine. At 2:26 a.m. on the 18th, Christopher, using the handle @VrilGod, tweeted, “Gonna ask a Priest if I should become a husband or shoot up a synagogue and die.” He added, “This time I’m really gonna do it.”

It was almost exactly four years since a gunman had entered the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh and murdered 11 people.

A Citywide Manhunt

The threat to shoot up a synagogue, coming just ahead of the Sabbath, caught the attention of a Jewish organization called the Community Security Initiative, which monitors internet forums for antisemitic threats. They set off a multiagency hunt for VrilGod.

At midday on Nov. 18, Matthew and Christopher met at St. Patrick’s Cathedral — to seek a “blessing,” Christopher later told the police — then drove with Jamil Hakime to the Poconos to get the gun. (Hakime ultimately pleaded guilty to transporting a gun across state lines and was sentenced to 27 months in prison.) In the backpack he carried, Christopher had a swastika armband, a knife and a ski mask.

By the afternoon, agents had identified VrilGod as Christopher T. Brown, of Aquebogue, N.Y.

Officers called Christopher’s cellphone, reaching him on the drive to Pennsylvania.

“They identified themselves as a detective, and asked if I had Twitter,” Christopher said by email. “I promptly hung up.” At that point, he said, “I got scared, and that is when I told Matthew and the driver we had to turn back.” But he said Hakime told Matthew to get his “boy” under control, and they carried on.

The police, fearing an imminent terrorist attack, issued an alert to all units to “be on the lookout” for Christopher, warning that he was “considered armed and dangerous.”

Matthew and Christopher returned to Matthew’s family apartment, where they dropped the gun — “I didn’t trust Chris with it,” Matthew said — then rode the subway to Penn Station so Christopher could get a train home to Long Island.

Stars of David that were issued to the Mahrer family during the Holocaust at the Mahrer family residence on the Upper West side of Manhattan.

Stars of David that were issued to the Mahrer family during the Holocaust at the Mahrer family residence on the Upper West side of Manhattan.Shortly before midnight, the police and F.B.I. agents surrounded them, guns drawn. As Christopher remembers it, he saw all the guns and asked one officer, “Is this really necessary?” After Arrest, Renewa

On Christopher’s first phone call from the Rikers Island jail complex, his aunt Maureen Murray said, she immediately noticed a change in him. “He said the first thing he got when he got to Rikers was a full night’s sleep,” she said. “And he hadn’t had it in ages.”

He was also finally receiving some psychiatric care — he was given a diagnosis of PTSD — and proper medication. He was a different person, his mother and sister said.

Denied bail, he befriended a Hasidic inmate, who introduced him to one of the jail’s chaplains, Rabbi Gabriel Kretzmer-Seed. Christopher began attending regular services and switched his religious affiliation to Judaism, the rabbi said.

“He definitely seemed sincere,” Rabbi Kretzmer-Seed said. “I remember him saying he regretted whatever pain he had caused, and definitely seeking forgiveness — wanting to do a 180 from being hateful towards Jews to wanting to explore Judaism seriously.”

During his two years at Rikers, he subsequently changed again, to Islam, which he said brought him peace and “a sense of true belonging.”

Because the only charges against Matthew were for possession of a weapon, he was granted bail, but he had another problem: News reports suggested that he and Christopher had together plotted to wreak antisemitic terror, even though only Christopher had made the threats.

Influential figures — including the district attorney, several rabbis and a City Council member — moved to have Matthew’s bail revoked, calling him a danger to the community. Neighbors campaigned to ban him from the apartment building.

Yet Matthew had known nothing about Christopher’s threats until after their arrest, both men said. The Mahrers felt blindsided. Their Jewish son had been made “a poster boy of antisemitism and neo-Nazism,” his mother said.

But he was also changing emotionally, in ways they did not expect.

Matthew Mahrer, days before he would be sentenced to two and a half years in prison for criminal possession of a weapon.

Matthew Mahrer, days before he would be sentenced to two and a half years in prison for criminal possession of a weapon.After his parents posted bail of $300,000, he was transferred to a psychiatric unit at Elmhurst Hospital Center. There he met a former inmate who was working as a peer counselor to others dealing with mental illness. It was a revelation, Matthew said.

He enrolled in a training program for peer counselors, where he found a purpose that he had never had — to use all his experiences to help people like himself, before they got into the criminal justice system. It is what he meant by post-traumatic growth.

Matthew was also assigned a social worker and care team and placed in a therapy program — what his parents had been trying to find for years.

With focused, appropriate therapy, he was able to stop all his medications for the first time since kindergarten.

“This is the one time that I feel like I was not failed by the system,” he said.

‘I Saved Him’

Last fall, nearly two years after their arrest, Christopher pleaded guilty to terrorism charges and was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Matthew pleaded guilty to criminal possession of a weapon. At his sentencing, as the Mahrers watched their son taken away to serve two and a half years in prison, they were left with the irony that it took his arrest for him to finally get the care he needed and to find direction for his life. And now the courts were taking these away.

From the prison upstate, Christopher was still at a loss to explain his actions that day. He and Matthew had been close to disaster, including “suicide by cop,” but also close to turning the car around, moving on with their lives.

Matthew said he did not blame Christopher for ruining his life. “In a weird way,” he wrote from prison, “I’d like to think he saved it, the way I saved him when I took that firearm off his person.” He later added: “I’d rather be in here than on the outside knowing I helped my best friend commit suicide.”

Matthew and Christopher both say they have received no therapy in prison, despite their diagnoses.

The mental health care system helped produce the two men who were in the car that day and also the progress both have made since. The products of that care will return to society as still young men, their lives ahead of them but forever linked to a potentially horrific event.

From prison, Matthew still talked about post-traumatic growth, about using his experiences to help others. His parents worried that being around criminals will undo the therapeutic progress of the last two years. On a three-way call in January, Matthew shifted abruptly in tone, declaring himself a gangster in a kill-or-be-killed environment. His mother tried to redirect him.

“Every day you’re moving past it, Matthew,” she said, treading what seemed like familiar ground. “Every day is one day closer to putting it in the past.”

At her words, he settled a bit, talking again about constructive plans.

After the call, his mother sighed and repeated a phrase from our first conversation, acknowledging the uncertainties yet to come: “We always called Matthew our work in progress.”

The Ukrainian teens who took on Putin's gulag archipelago — and won

When Vlad and his friends realized the Kremlin would not return them home, they staged an open revolt.

By CASEY QUACKENBUSH in Kyiv

Portraits by Sasha Maslov for POLITICO

March 26, 2025 4:00 am CET

![]()

I

Camp Druzhba

November 2022

As the sky began to darken, Vladyslav Rudenko slid a pair of underwear into his hoodie and pretended to go for a walk. The 16-year-old Ukrainian boy had to hurry. He only had a slim window of time before the lanterns lit up the campgrounds of the reeducation camp, potentially exposing him to the Russian counselors.

He left his dorm alone around 6 p.m. and wound through the campus enclosed by a two-meter-high fence topped with barbed wire. He arrived at an outdoor stage overlooking an open square where the camp’s children were required to gather every morning to sing the Russian national anthem. Vlad climbed up the stairs of the stage, dodging the security camera pointed right at it, and turned right toward a row of flag poles: a rainbow flag for the camp; another for occupied Crimea; and the blue, red and white flag of Russia.

“Why should that be hanging there?” he thought to himself. The Russian flag didn’t represent him, a boy from the Ukrainian city of Kherson. It represented the armed men who took him from his home in balaclavas. What really belonged there, if not the Ukrainian flag, was his underwear.

Vlad did one last scan to ensure no one was around and then grabbed the rope on the flagpole. He untied it and tugged, lowering the Russian flag as fast as he could. Once it reached the ground he unhooked it, fastened his underwear and hoisted it up the 4-meter pole. He felt his eyes popping out, his heart dropping to his stomach — the flagpole was so high — and then, a resistance. Vlad looked up and saw his blue and white checkered boxers hanging in the twilight.

“Yep,” he thought. “That’ll do.”

At first, Vlad felt overjoyed, having pulled off the most audacious stunt the camp had seen. “A story to tell to my kids,” he said. Then, his joy turned to fear. In the eyes of the Russian authorities, this was not a teenage prank. It was treason. He had to dispose of the flag immediately. He bunched it up, stuffed it under his hoodie and ran to the nearest bathroom where he met a friend. The two boys proceeded to tear the Russian flag apart, throw the pieces in the toilet and relieve themselves on it. They filmed the act with their phones and then flushed the defiled flag down the toilet. They snuck back to their rooms where they rewatched the video over and over again, laughing into the night.

![Oleksandr and Anton believe that the scandal in the White House was deliberately caused by the USA.]()

At 8 a.m. the next morning, there was a stir near the flags. Usually, Vlad and his friends did everything they could to avoid the anthem ritual. That morning, he made an exception. He went outside, where some guys approached Vlad and excitedly explained what had happened. “Wow,” said Vlad. “Those who did it are cool!” He saw his underwear on the ground and tried his hardest to keep a straight face as the head of security questioned the campers. “Good thing no one knows it was me,” he thought. Portraits by Sasha Maslov for POLITICO

March 26, 2025 4:00 am CET

I

Camp Druzhba

November 2022

As the sky began to darken, Vladyslav Rudenko slid a pair of underwear into his hoodie and pretended to go for a walk. The 16-year-old Ukrainian boy had to hurry. He only had a slim window of time before the lanterns lit up the campgrounds of the reeducation camp, potentially exposing him to the Russian counselors.

He left his dorm alone around 6 p.m. and wound through the campus enclosed by a two-meter-high fence topped with barbed wire. He arrived at an outdoor stage overlooking an open square where the camp’s children were required to gather every morning to sing the Russian national anthem. Vlad climbed up the stairs of the stage, dodging the security camera pointed right at it, and turned right toward a row of flag poles: a rainbow flag for the camp; another for occupied Crimea; and the blue, red and white flag of Russia.

“Why should that be hanging there?” he thought to himself. The Russian flag didn’t represent him, a boy from the Ukrainian city of Kherson. It represented the armed men who took him from his home in balaclavas. What really belonged there, if not the Ukrainian flag, was his underwear.

Vlad did one last scan to ensure no one was around and then grabbed the rope on the flagpole. He untied it and tugged, lowering the Russian flag as fast as he could. Once it reached the ground he unhooked it, fastened his underwear and hoisted it up the 4-meter pole. He felt his eyes popping out, his heart dropping to his stomach — the flagpole was so high — and then, a resistance. Vlad looked up and saw his blue and white checkered boxers hanging in the twilight.

“Yep,” he thought. “That’ll do.”

At first, Vlad felt overjoyed, having pulled off the most audacious stunt the camp had seen. “A story to tell to my kids,” he said. Then, his joy turned to fear. In the eyes of the Russian authorities, this was not a teenage prank. It was treason. He had to dispose of the flag immediately. He bunched it up, stuffed it under his hoodie and ran to the nearest bathroom where he met a friend. The two boys proceeded to tear the Russian flag apart, throw the pieces in the toilet and relieve themselves on it. They filmed the act with their phones and then flushed the defiled flag down the toilet. They snuck back to their rooms where they rewatched the video over and over again, laughing into the night.

For the next few days, Vlad did his best to fly under the radar. The camp, home to about 600 captive Ukrainian children, was called Druzhba, which means “friendship” in Ukrainian and Russian. It is part of a vast archipelago of similar institutions, sprawling from the Black Sea to Vladivostok, set up by the Kremlin to indoctrinate Ukrainian children.

Ukraine says that almost 20,000 Ukrainian children from the ages of 7 to 18 have been illegally taken from their homes in occupied territory. Russia, which has defended its actions as a humanitarian effort rescuing children from a Nazi-ridden Ukraine, has boasted of “accepting” more than 700,000 children. But those numbers include whole families and are not specific to child deportation, and the exact number of missing Ukrainian children remains unknown. Since the beginning of the conflict, at least 1,243 have returned.

These sorts of camps date back to the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin, who used them to indoctrinate or “Russify” Soviet children of other ethnicities. Today, in an effort to wipe Ukrainian children of their nationality, President Vladimir Putin has redeployed some of the same infrastructure to offer what the Russian government describes as a patriotic education.

The effort has drawn international condemnation. In 2023, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Putin and his commissioner for children’s rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, for forcibly deporting children, which is a war crime.

In December, a new report from the Yale School of Public Health upped the ante: It found Putin and Kremlin officials guilty of leading a program of systematic coerced adoption, fostering and naturalization of Ukrainian children, which may constitute a crime against humanity. But recently, the Trump administration’s DOGE initiative terminated Yale’s research, which was funded by the State Department, throwing those charges, and the fate of abducted Ukrainian children, into jeopardy.

“These camps, now and then, were about severing family unity and national identity that conflicted with the then Soviet state,” said Nathaniel Raymond, a human rights investigator who led the report. “And now, Putin’s Russia.”

But there is a fundamental flaw in Putin’s project: There is perhaps no group of people on the planet that despises being told what to do and who to be more than, well, teenagers.

As soon as Vlad and his friends realized the Kremlin would not return them home, they staged an open revolt. As Russian authorities moved them from institution to institution, telling them that Ukraine would be part of Russia and that their parents no longer wanted them, the teenagers did what they could to resist. The disobedience was often met with cruel punishment. And yet, they remained defiant, deliberately violating the rules — for fun, and for survival.

“They were trying to break us,” said Vlad. “And we were breaking them in return.”

II

Camp Druzhba

Oct. 7, 2022 – Dec. 22, 2022

In October 2022, the city of Kherson was under occupation. Russian soldiers stalked the streets. They raided homes, tortured dissidents and took over all the major institutions, including the lyceum of Denys Berezhnyi, who was studying to become a mechanic. One day Denys was at school when six armed soldiers came to his classroom and told everyone to pack their things for camp. “We know where you and your parents live,” they said.

That evening, Denys went home to notify his parents. No papers were signed, no consent was given, but there was nothing they could do. The next day, Denys boarded a bus and then a ferry across the Dnipro River to Oleshky, a city even deeper into Russian-occupied territory, where he awaited yet another bus with almost 300 other kids. Despite the sudden departure, part of him was looking forward to camp. The authorities had presented it as a chance to relax on the beautiful Crimean peninsula for two weeks, a welcome change after eight exhausting months living under occupation. Maybe he’d even have some fun for once.

“We joked around and laughed,” said Denys. “But

after a while, it wasn’t funny anymore.”

He boarded the bus, for what turned into a miserable eight-hour journey with no stops. If Denys wanted to pee, it had to be out of the bus window. As they trundled through the war-torn southeast, Denys’ only joy was the sight of burnt-out Russian military equipment. The only other familiar face on the bus was a 17-year-old classmate named Serhiy Kozulin. Originally from the Krasnolyubets’k village in north Kherson, which was devastated during Russia’s initial offensive, Serhiy enrolled in school in the city so he could have internet access. When Serhiy was taken, he couldn’t reach his mother back at home.

In the middle of the night, Denys and Serhiy arrived in Yevpatoriya, a Black Sea resort town in Eastern Crimea, which Russia had illegally annexed in 2014. The bus pulled into Druzhba’s only entrance. The next morning, they met Valeriy Astakhov, a tall bald man in charge of camp security.

Astakhov was once an officer in the Berkut, a notorious Ukrainian riot police unit that brutally cracked down on the pro-European Maidan protesters in 2014. He later defected to Russia and participated in the forced deportation of Ukrainian children from the occupied Donetsk region in 2014 — a warmup to the wholesale effort that swept up Denys and Serhiy. The boys also met the camp counselors, a cohort of Russian 20-somethings sent to Druzhba for practical training with kids.

Astakhov laid out the rules. Leaving campgrounds was forbidden. No smoking, no drinking, no Ukrainian anything. Any flags or T-shirts would be torn up. “There will be no kastrulias here,” he said, a derogatory term for Ukrainians meaning “pots.” As the days went on, their new reality set in. Every day, the campers were required to line up for the Russian anthem at 8 a.m. and locked in their dorms at 10 p.m. The food was bad: tasteless, no salt, sometimes with hair in it. They could not receive packages. After being denied sufficient care for his Type 1 diabetes, Denys rationed his insulin and landed in the hospital for three weeks. If the kids needed more layers as it got cold, they were told to pick from a pile of secondhand clothes on the floor.

Their teenage rebellion began immediately. Driven by hunger, anger and boredom, the boys found the CCTV surveillance gaps in the fenceline and broke loose. They started sneaking out to the local store for sausage, bread, snacks and kvass, a beer-like alcohol. During the assemblies to sing the Russian anthem, they refused to participate.

Led by Serhiy’s roommate, Rostyslav Lavrov, a 16-year-old boy who goes by Rostyk, from the Radensk village of Kherson, the three boys would sit on a bench, walk away or just not show up at all. For this, Rostyk was forced to write reports on why he did it. He landed in the office of Astakhov, who threatened that if he kept refusing to conform, he would be sent to a boarding school or psych ward.

The two-week stay became three, and then four. As October dragged into November, the boys could tell something had gone very, very wrong.

Every week, Astakhov gathered the kids for an announcement: The bus is coming … the bus is late … the bus got shot. But the boys had their phones and access to the messaging app Telegram. They knew the truth: The Ukrainian army had liberated Kherson during a counteroffensive on Nov. 11, 2022.

The feeling was bittersweet. On one hand, their homes and families were free. On the other, there was no way the Russians would return them to Ukrainian territory now. Eventually, Astakhov admitted it. “He said no one needed us anymore,” said Rostyk. “And that in another month, Ukraine would no longer exist, that it would all be Russia.”

This news unleashed a wave of unrest among the teenagers. They wanted nothing to do with the camp activities — the anthem, the discos, the lessons. The next day, Serhiy and Rostyk were in their room when Serhiy suggested they stage a sit-in. “Let’s lock ourselves in so they won’t bother us,” said Serhiy. Rostyk agreed. In preparation, they stocked up on food from the store: noodles, cookies, candy, bagels and water. In the morning before breakfast, they locked the door, pushed a wardrobe in front of it and waited.

It wasn’t long before they heard a knock on the door. They put their headphones in, turned on music and kept quiet. “Open up, we know you’re in there,” said one of the counselors. Silence. The counselors threatened them with solitary confinement. Silence. The counselors left then returned with Astakhov. “We’re not going to open the door,” said Rostyk. “We don’t want to.”

Down the hall near Denys’ room, another boy rallied kids from around the dorm. “Come to my room if you want to talk about the fact that we’re not going home,” he said. About 30 gathered to discuss. The next day, Denys and about half of the group barricaded themselves in another five or six rooms — the others declined, fearing the consequences. Denys stocked up on food, pushed a wardrobe in front of the door and refused to answer. When the counselors noticed the kids were missing, they knocked then tried to break in.

“Let us all go home, and then we’ll stop,” said Denys.

“What can we do about it?” one counselor said. “It’s not up to us.”

The counselors were largely Russian students trying to fulfill school credits. Sometimes they were mean, sometimes they bought cigarettes for the kids and sometimes they were indifferent, especially when outnumbered. The main source of cruelty at camp was Astakhov. Children who later returned to Ukraine reported that he locked children in basements at Druzhba and beat others with an iron bar at another camp. He cut off a T-shirt bearing a Ukrainian flag from a 15-year-old girl named Taisiya, then filmed her for a propaganda video while she cried. He sent a 12-year-old boy named Mykyta to a mental hospital.

Neither Astakhov nor the commissioner for children’s rights responded to requests for comment.

And then there was Vlad. In the days after his underwear prank, the counselors tried to weed out the culprit. He didn’t dare joke about what he had done in public, and he and his friend deleted the video. On day four, during quiet time after lunch, Astakhov entered Vlad’s room unannounced. The former riot cop came with a counselor and closed the door behind him.

Astakhov gave Vlad two choices: the isolation ward or the police station. Vlad chose the former — at least he’d know what to expect. Astakhov asked him where the flag was. Vlad said he had left it on the nightstand, but that it went missing. “Really?” said Astakhov. “Yeah, where else would I have taken it?” said Vlad. Astakhov told him to pack his things. Vlad first refused, but gave in after Astakhov started doing it for him. Vlad finished packing but still refused to leave the room, so Astakhov and the counselor grabbed him by the arms and hauled him to the medical center, which served as the isolation ward. Two friends followed him there and cried as they said goodbye.

When he arrived at the ward, he was told he would remain in solitary confinement for six days. His phone was taken away, and he was placed in a 2-by-2 meter room with a barred balcony. The walls were light green and it smelled like medicine.

Vlad pounded his fists against the walls and tried to break down the door. Astakhov told him if he calmed down, they would release him sooner. If not, they’d send him to a mental hospital. The nurse gave him eight pills, which he refused. He made such a commotion that on the fourth day they let him call his mother.

“Mom, I’m not OK here,” he told her. “I can’t stay here anymore. I might do something to myself. Do something, please.” It felt good to hear her voice, but he realized that he was helpless. He contemplated suicide.

“If I can’t make it,” he thought, “Then that’s my fate.”

On day six, he was released. He walked out and felt as if he had entered “another dimension.” The sun was shining. The plants were green. His friends collected him and carried his bags. No more sleeping alone. He could talk and listen to music. He was so full of joy. But the days after, he felt closed off, like 10 years had passed, and struggled to process what had happened. About a week later, he started to feel back to normal — even emboldened, so much so that he and a friend went to the canteen and removed the Russian flag again.

This sort of resistance was common among some of the older kids, but the younger ones were more timid. The counselors separated Vlad from his older group and bunked him with younger kids to prevent him from acting up. Every night, he could hear the younger kids wailing out, “Mommy, mommy,” and then being told to shut up. There was one 12-year-old boy nicknamed Baton, which means “loaf,” who cried every night. Through the walls, Vlad could hear the counselors take Baton out into the corridor and make him stand in the corner until the morning.

“I’d go to him and say, ‘Baton, everything will be fine. You’ll be going to your mom soon,’” Vlad recalled. “He’d whimper, ‘Yeah, I understand,’ then start crying again.”

“There was nothing we could do to help him,” said Vlad. “He just kept crying.”

III

Camp Luchystiy

Dec. 22, 2022 – Feb. 2, 2023

The mischief continued through December. Every couple of days, the boys would sneak out of their sit-ins to shower, smoke or walk and then shut themselves back inside. Rostyk was repeatedly put into isolation, during which time Serhiy snuck him a second phone and cookies through the barred windows of his cell. Vlad and his friends barricaded themselves on the top floor by jamming the stairwells with furniture and beds and even trapped counselors inside their rooms using tape and glue.

The protests only ended when it was announced that Druzhba was shutting down and merging with another camp about 45 minutes away called Luchystiy. On Dec. 22, rather than preparing to go home for Christmas, Vlad, Serhiy, Rostyk, Denys and about 200 other kids from Kherson were transferred.

It wasn’t long before the unrest resumed and escalated. Denys slept in the bathroom to avoid morning exercises. Kids hid alcohol in the ventilation systems. Then on New Year’s Eve, the campers staged a walkout. At midnight, Serhiy and a group of kids were in the camp theater when Putin’s New Year’s speech came on. They exited the theater and returned to their rooms, where Serhiy and several others set up speakers on their balconies and blasted the Ukrainian anthem and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s address to the nation.

Denys had been away for three months and was desperate to get home to his parents. He started exploring escape plans: contacting the Red Cross, hiring a private car or just running. But even if he somehow managed to escape, he would have been put on a wanted list. Ukrainian documents are not recognized in Russia, so he would not have been able to have purchased so much as a train ticket. Even if he got the money for a private car, he would not have been able to cross the Russian border without an authorized escort. All roads almost certainly led back to Astakhov.

Still, Denys remained determined. “If I lost my mind, I would have tried to find a way back home,” he said. He dreamt up plans but he kept them to himself. There was only one way Astakhov had learned about Vlad: informers. At camp, counselors rewarded tattlers with extra helpings at meals or trips to town. For the sizable group of pro-Russian kids among the campers, this was an easy deal. So Denys didn’t dare share his ideas with anyone, not even his friends. “Too many rats,” said Denys.

The only people he trusted were his parents. They had spotty cell reception back home in Kherson, but whenever Denys could reach them, he cried. Over video calls, his parents could see his withering and sallow cheeks. Meanwhile, they suffered high blood pressure, psoriasis and nosebleeds.

The Russian authorities had made it clear: If parents wanted their kids back, they would have to retrieve their kids themselves. But it was almost as unlikely for them as it was for Denys. With the entire southeast of Ukraine consumed by war, the only way to get to Crimea from Kherson would be to drive through Belarus then down mainland Russia — a 4,000-kilometer journey.

Denys’ parents sent him what money they could from their pensions so he could buy food and insulin, but the cost of the trip was prohibitive. And above all, it was dangerous. For Denys’ parents, both of whom are deaf, the risk of miscommunication with armed Russian soldiers at the border was too high.

“Overwhelming,” signed Denys’ father Dmytro, blowing air through waving fingers. “Impossible.”

IV

Kerch Maritime Technical College

Feb. 2, 2023 – July 5, 2023

It was late winter. The days were short and cold, and the boys were told once again to pack their things: They were being taken to college to study. To Serhiy, this seemed like a positive development. At least they would have some freedom to walk around off campus. “And if it didn’t work out, we could make an escape plan then,” said Serhiy.

In February 2023, Serhiy, Rostyk and Denys were taken to Kerch Maritime Technical College, a naval academy three hours east of Yevpatoriya. Rostyk and Serhiy were placed as roommates in one building. Denys was placed in another building, and Vlad was taken to an entirely different military college.

Kerch was not an improvement. At least at camp, the boys had been surrounded by other Ukrainians. At the college, they were the only ones. Forming a resistance became that much harder, especially after the boys came under pressure to apply for Russian passports. Within the first month, the Russian authorities called the boys into their office and offered them 100,000 rubles ($1,000), apartments and Russian passports.

“You understand that you’re in Russia now, you need to respect this country,” they said to Rostyk. “Since you’re living here, you need to get this passport.” When Rostyk resisted, the authorities threatened to cut his scholarship.

“Go ahead,” Rostyk told them. “Reduce it.”

For that, Serhiy and Rostyk were confined to their dorm for two weeks in April. Luckily, they had befriended some sympathetic Russian kids on the first floor, who let the boys use their window to sneak out and go into town, shop and smoke. When they got out of confinement, the pressure resumed.

The weaponization of passports is a common tactic deployed by the Russians in the occupied territories, in which access to a normal life, from social benefits to purchasing property, becomes nearly impossible without taking on Russian nationality.

This put the boys in a difficult position. After so many months of living in limbo, here was a path toward security. But if they gave in, a passport would qualify them for adoption in Russia, the changing of their names and a military draft that, once they were 18 years old, could put them on the front lines fighting against their home country.

The boys remained defiant, but six months into captivity, they were running out of hope and options. “By then, I had resigned myself, rather than looking for a way out,” said Denys.

Back in Ukraine, however, their families were hatching an escape plan. Serhiy’s mother had contacted Save Ukraine, a charity that organizes rescues of abducted Ukrainian children by Russia. In a now-deleted report, Russia’s commissioner for children’s rights designated the group a terrorist organization.

Save Ukraine’s rescues are not dramatic, dead-of-the-night operations. They are more of a mission through the underworld of Russian bureaucracy. Each child’s case is different. Save Ukraine ironed out the plan for Serhiy, Rostyk and Denys: Serhiy’s mother Iryna would travel to Crimea to retrieve all three boys from Kerch. But for that to work, Iryna would have to effectively become the legal guardian of Serhiy’s friends, since Denys’ parents were alive but disabled, and Rostyk’s mother was located in an unknown mental hospital. For two months, Save Ukraine hunted down the necessary documents. In early June, 2023, Iryna set out for Kerch.

The boys were vaguely aware of the plan. Serhiy had hidden his passport with a local friend so the Russians couldn’t steal it. He was right to be concerned. In the run up to Iryna’s arrival, Serhiy, Rostyk and Denys were barred from leaving their dorms, even though the college authorities had already approved all of Iryna’s documents. They remained confined to their rooms for a week until Iryna arrived, at which point Serhiy and Denys were called to the director’s office.

Serhiy cried upon seeing his mother. He and Denys were free to go. But Rostyk was not. The Russian authorities claimed that his mother was in a mental institution in Crimea, and that if Rostyk wanted to leave, she would have to come for him herself.

Rostyk’s case had to go to a trial, which would determine whether Iryna had the right to take him. Iryna left the campus with Serhiy and Denys, but they hid in Crimea with their phones turned off to await the outcome. Meanwhile, the Russians locked Rostyk in his room to ensure he didn’t run away. After two weeks, however, the trial was postponed. Iryna and the boys had little choice but to get out.

Rostyk would find his own way back months later, but Serhiy, who couldn’t know that, was devastated. “We had so many plans!” said Serhiy. “We wanted to go for a ride [on my motorbike], to walk around. I’d already told the girls [at home] I’d be coming with a friend. And then I arrived alone, and for a month they kept asking, ‘Where’s your friend?’”

The next few days on the road were a long, exhausting blur. Save Ukraine asked to keep the details of the journey home confidential so as not to jeopardize future rescues, but it took about five days to drive northwest through Russia and then into Belarus. At the border, the boys were interrogated. Just when they thought they were out, the agents asked for one more document, one they did not have. They were 2 kilometers from the Belarusian border.

After a few long moments, they were allowed to pass. “Alright,” said the agent. “Go on.”

“What fools,” thought Serhiy.

Denys and Serhiy continued through Belarus to the border with Ukraine. Before crossing, they stopped to smoke cigarettes and looked at their Russian migration cards. “We have to burn this shit,” said Serhiy.

Standing in the middle of the road surrounded by security cameras, Denys and Serhiy took their lighters to their migration cards. For about five minutes, the flame licked away at the lamination, slowly consuming the plastic and emitting a blue smoke. They finished their cigarettes, and threw the remnants of their cards over the guard rails into a zone full of mines.

They kept walking, and after a turn, they saw the Ukrainian flag hanging. Metal, anti-tank hedgehogs were scattered along the road. No one was around. As they approached the border, a soldier emerged and asked, “Citizens of Ukraine?”

“Yes,” the boys replied.

He approved their documents, offered the boys a wheelbarrow for their bags and they walked into Ukraine.